Note: I’m currently offering a special 30% discount on a one year paid subscription, meaning just one payment of $35 for full access to the weekly newsletter. The offer is available through September 12th.

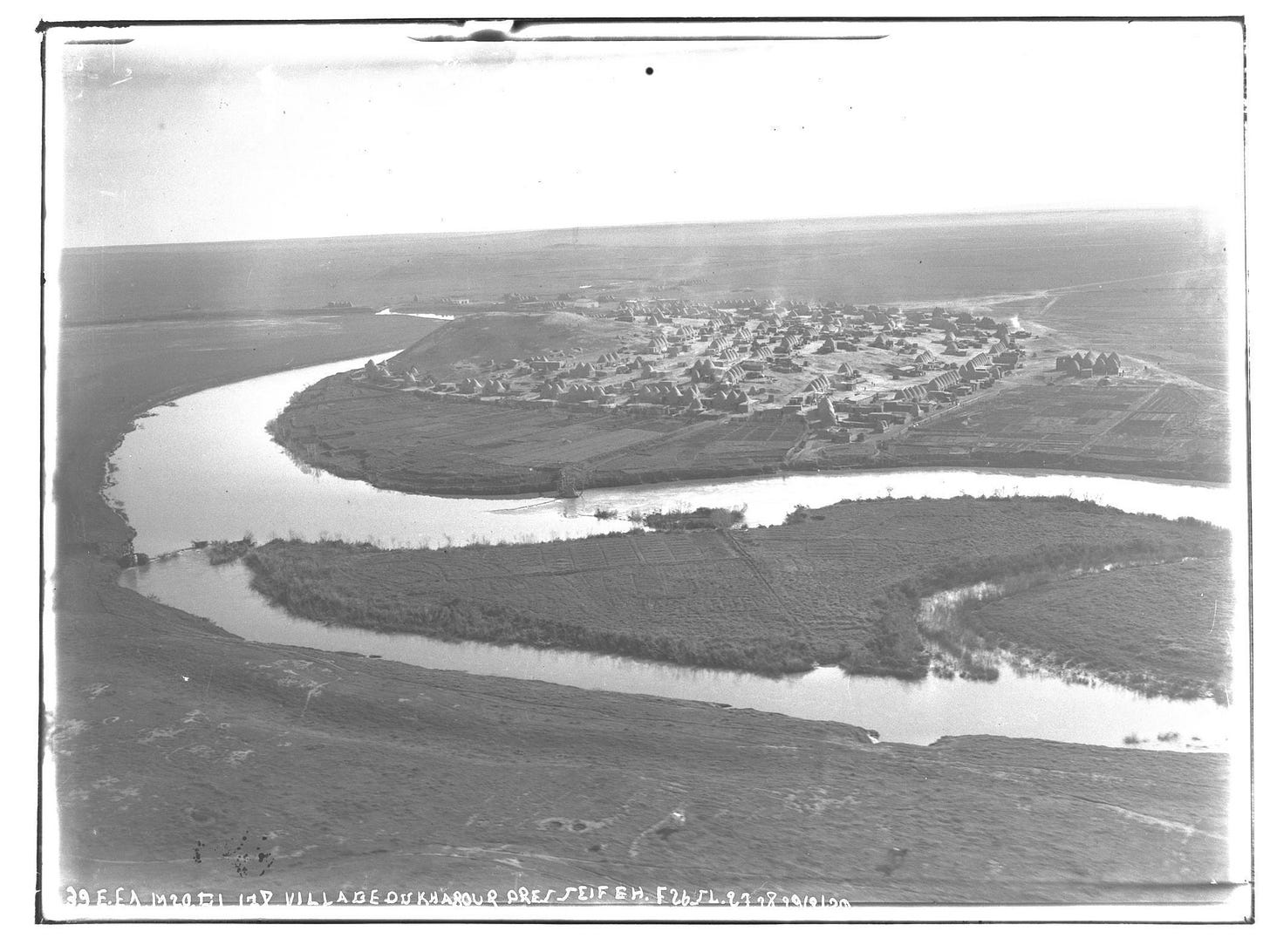

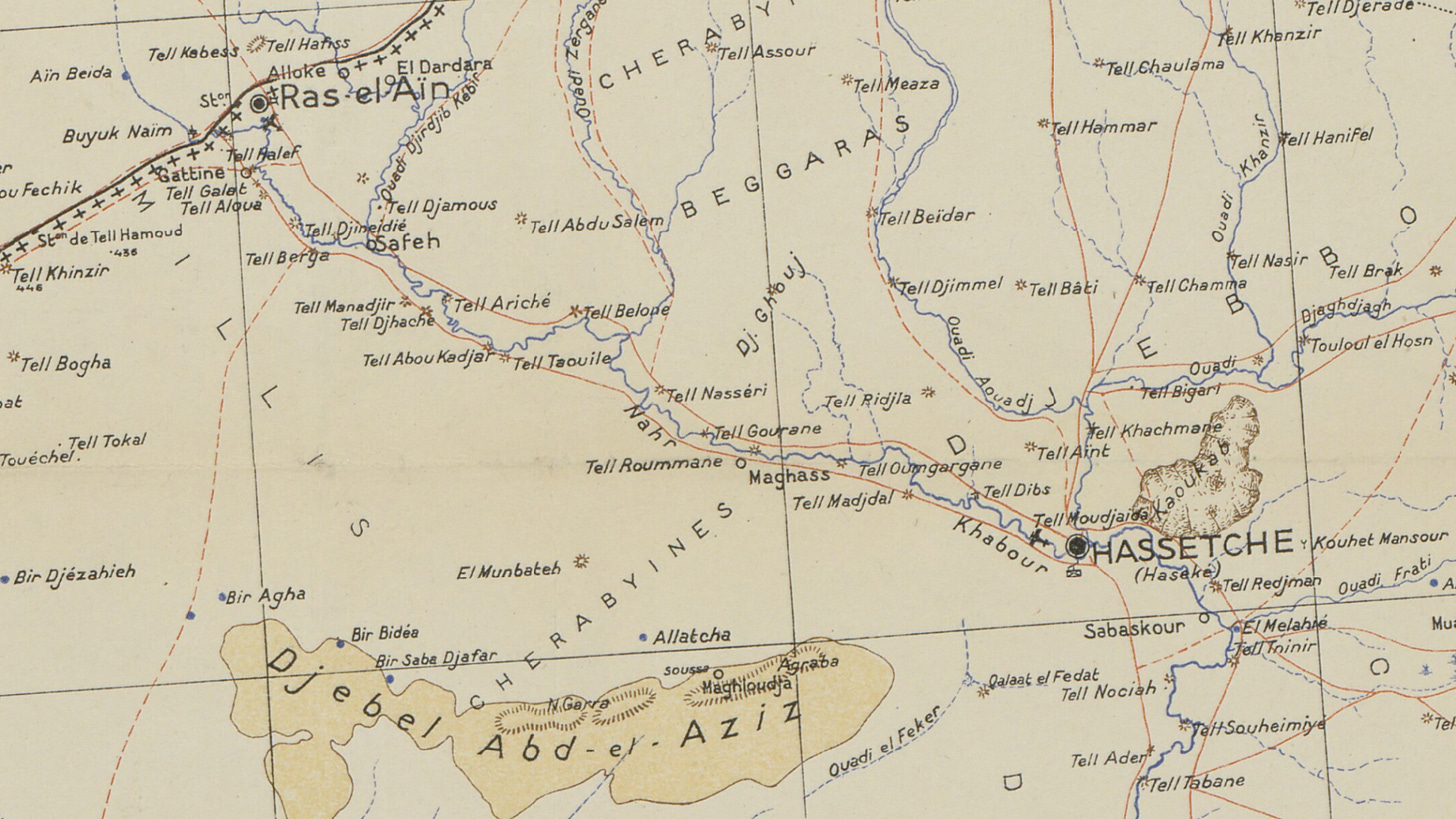

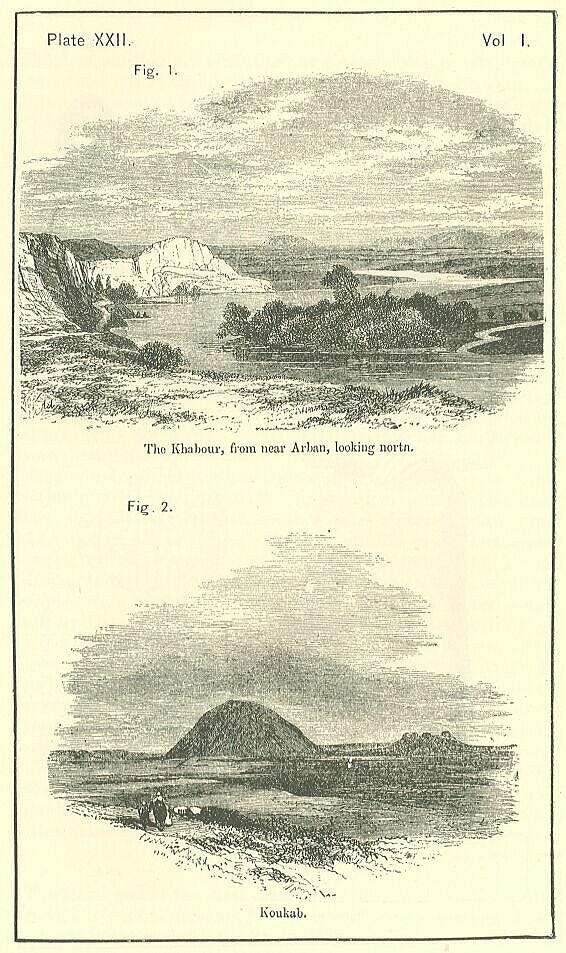

The Khabour river is the largest tributary of the Euphrates, entering Syria via Turkey at the town of Ras al-‘Ain/Serê Kaniyê in northwestern al-Hasakah. From there it snakes east, meeting the Jaghjagh river on the eastern outskirts of al-Hasakah city before turning south, emptying out into the Euphrates around the town of al-Busayrah in central Deir ez-Zour.

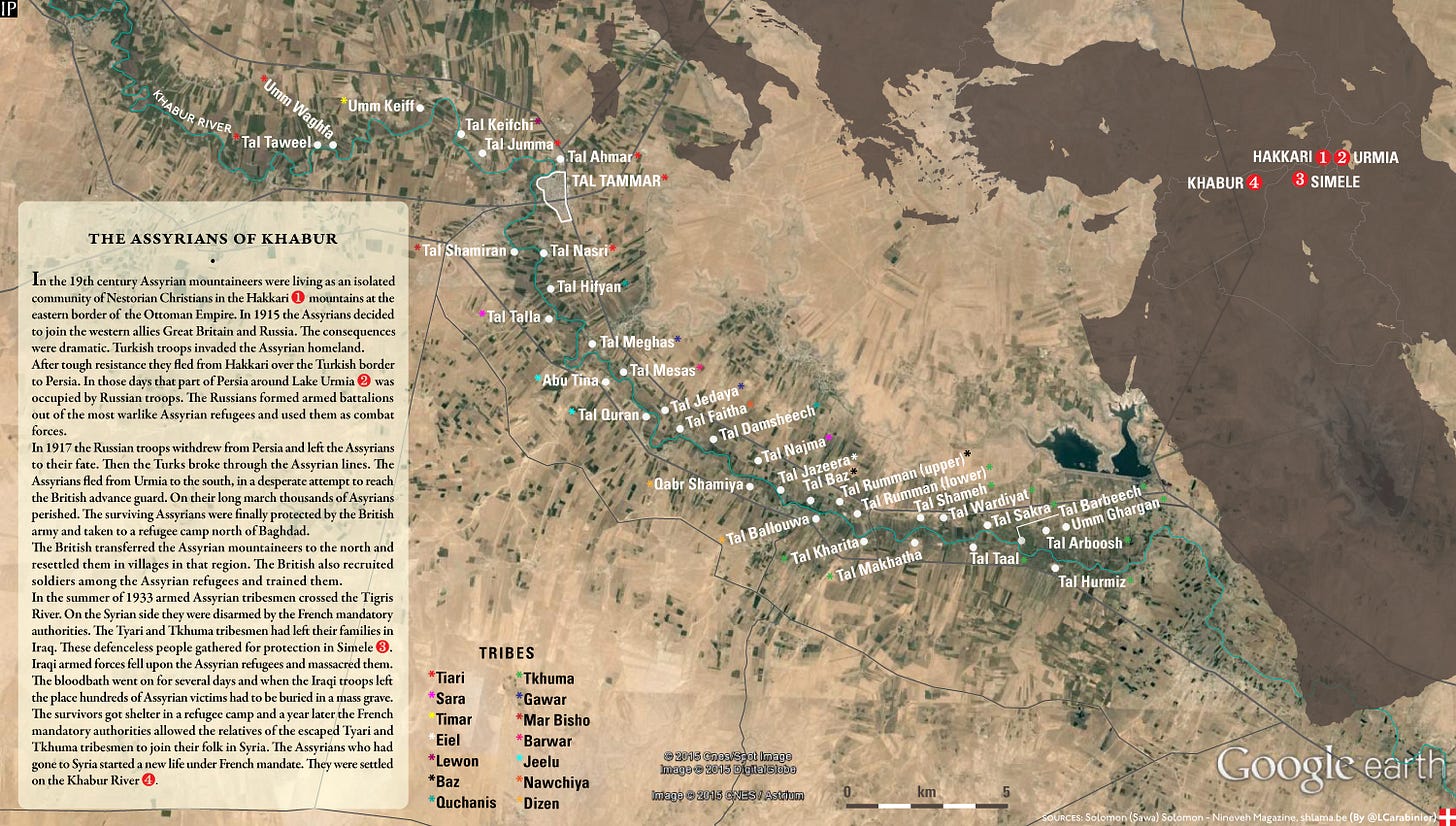

Most notably the upper Khabour is home to Syria’s main Assyrian community, residing in a several dozen villages stretching from Tell Tamer - a mixed Kurdish/Arab/Assyrian town to the Western dam - a dam just north of the Khabour on one of its tributaries. This Eastern Neo-Aramaic speaking population was settled here in the 1930s, double refugees who first fled their homeland of Hakkari during the Assyrian genocide of 1915 for northern Iraq where they were later targeted by the newly-independent Iraqi military in Simele Massacre of 1933.

In a 2009 Assyrian magazine piece on the region it was estimated that the local Assyrian population numbered 10,000, down from a high point of roughly fifteen thousand at the end of the 20th century. Most of the community belongs to the Assyrian Church of the East, which “claims continuity with the historical Church of the East” - contentiously referred to by some as Nestorian Christianity due to its association with dyophysite theologian Nestorius of Constantinople (386-451). Residents of villages Umm al-Kaif, Tell ‘Ashnan Gharbi, Tell Kifchi, and Tell Hormiz (and possibly others) are members of the Ancient Church of the East, a splinter formed in 1964 in opposition to Assyrian Church of the East’s transition from the Julian to Gregorian calendars. Meanwhile Tell Arbosh is reportedly the only majority Chaldean Catholic village in the region (the result of a 16th century schism within the Church of the East).

In February 2015 the Islamic State launched an offensive targeting the upper Khabour from nearby Jabal ‘Abd al-‘Aziz to the south. The jihadists took hundreds of Assyrian civilians captive, while destroying churches and looting houses. Despite the region soon being recaptured by the SDF and the captives being ransomed, most the Khabour Assyrians fled with few returning to this day.

Much less know is the historical Chechen–Ingush population found in Ras al-‘Ain and nearby settlements around the Jirjib tributary of the Khabour. Researcher Han Scholl, a spiritual forefather to this publication, mapped some of the limited information available on this community back in 2017.

This map intends to show the historical progression—or, more accurately, contraction—of the settlement area by dividing those rural villages attested in available sources into three “layered” groups. The villages listed as current settlements in this article published in June 2017 by Souriatna, an outlet aligned with the Syrian opposition, are presented with unbroken circles as the most recent layer; al-Safih, as the most significant of these presently and historically, I have marked more prominently. The next layer comprises those villages attested by Ahmad Zakarya in his in-depth mid-1940s survey of Syria Asha’ir al-Sham (p. 702), presented with dashed circles. The remainder of the villages, marked with dotted circles, are those not included in either of the aforementioned sources but are attested in other sources (particularly this selection by Madina Khangoshvili, found in a 2014 post on a community interest website but apparently originally published in the Annals of the Academy of Sciences of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria in April 1999) as being inhabited earlier or without clear date, and are assumed to be either those villages whose original Vainakh inhabitants had emigrated or assimilated prior, or possibly whose populations were simply missed in the later surveys. The mixed town of Ras al-‘Ayn also presently retains a Chechen population dating back to the community’s original establishment, but as a quasi-urban location it is not specially marked with a circle on the map.

Chechens and Ingush entered the area in the mid 19th century following Russia’s invasion of the Caucasus and the Ottoman empire’s ensuing defensive strategy of settling various Caucasian refugees (most notably Circassians but also Abkhazians and others) in between civilization and the steppe/desert. Despite their rich history in antiquity, prior to the entrance of these Chechens and Ingush (as well as the later settlement of Assyrians during the mandate period) the general area was quite empty, with Arab nomads from the south and Kurdish nomads from the north passing through seasonally.

According to the first piece linked in the above quote in 2017 there are approximately 3,000 Chechen families in the Ras al-‘Ain area, though it’s unclear what percentage of the community still speaks the language. One member of the local Chechen community can be seen and heard playing the accordion throughout the trailer for 2016 documentary My Paradise, about the town and director Ekrem Heydo’s childhood friends and their diverging fates over the course of the war (prior to the 2019 Turkish invasion).

During the aforementioned invasion Hans Scholl also made this map of volcanic formations along the upper Khabour, highlighting several key topographical features relevant to the conflict.

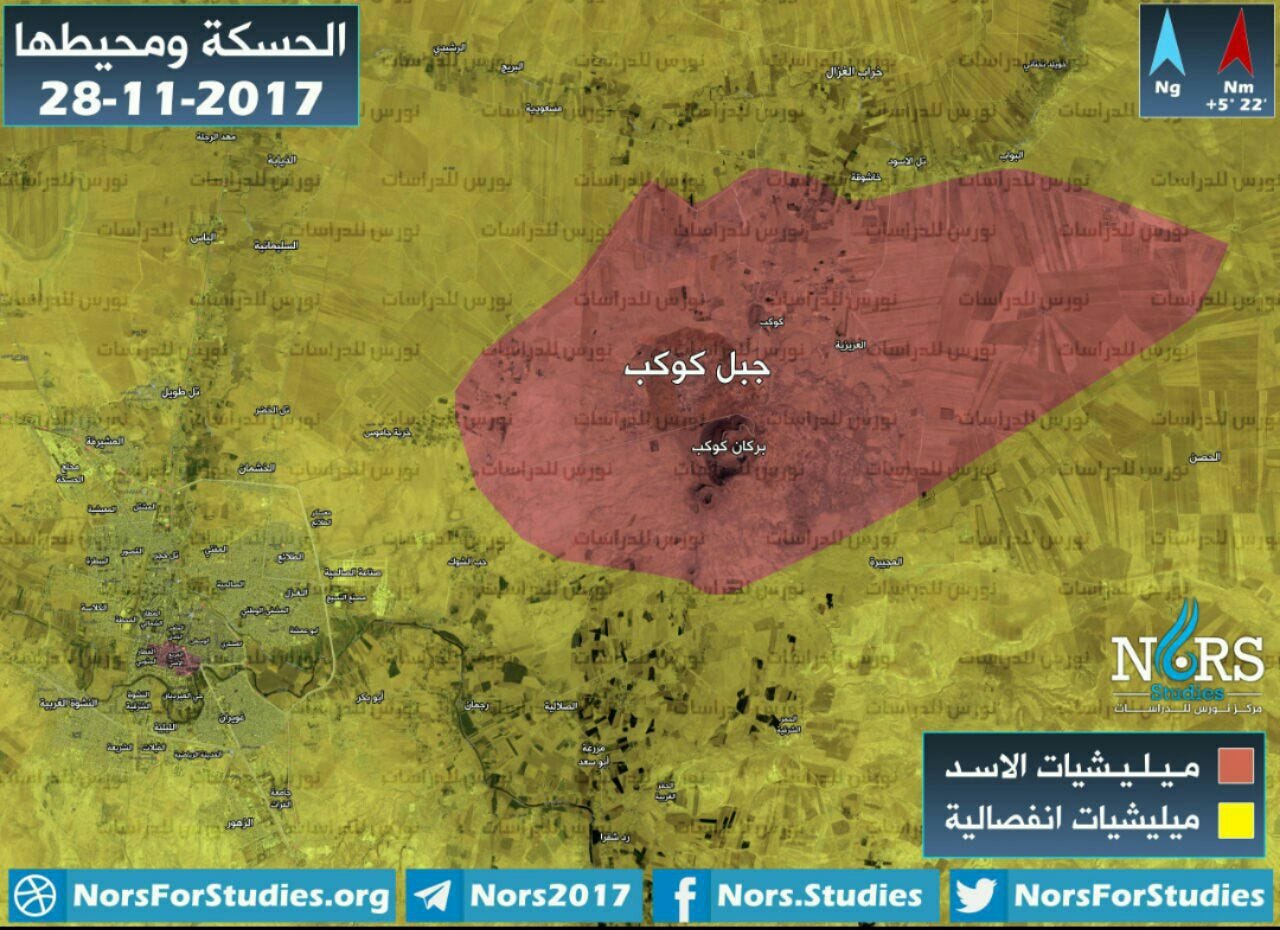

The Abdulsalam hills located on the SNA/SDF front lines just northwest of Tell Tamer are the now the site of several Turkish military bases bases. One of the biggest American military bases in Syria sits atop Jabal Qulayb (aka Ghouj or Ghoul). Meanwhile Jabal Kawkab sits within what was a former regime-controlled pocket outside al-Hasakah city for the entire extent of the war, home to military base and communications center on its peak.

Other key sites on the upper Khabour include the US military base located at the end of the Western dam (sometimes referred to as Istrahat al-Wazir), the adjacent SDF leadership compound at the former Live Stone resort, and the Washokani IDP camp (see below) that houses Ras al-‘Ain natives displaced by the 2019 Turkish invasion.