Roger Lescot's "Kurd Dagh and the Muroud Movement" (1940) part I

On a Sufi-led populist movement in French Mandate Afrin

This is a booklet written in 1940 by French orientalist, diplomat and Kurdophile Roger Lescot on the Muroud, a populist movement that sparked serious unrest in 1920s Afrin. The Muroud was led by a Naqshbandi sheikh from Turkey and while it appears to have started as a religious revivalist movement eventually came to challenge the region’s landed elite and, in the 1930s, the French occupation of Syria.

I first encountered the Muroud in Harriet Allsopp’s The Kurds of Syria: Political Parties and Identity in the Middle East (2016) in which she briefly highlights the movement along with the Xoybûn, the Kurdish-Christian autonomist movement of the Jazirah, and the Syrian Communist Party (SCP) as the primary examples of Kurdish political organization in Syria prior to the 1957 creation of the Kurdistan Democratic Party of Syria (KDPS), the first Kurdish nationalist party founded in Syria by Syrian Kurds. Allsopp also uses the Muroud (and the SCP) to emphasize Afrin’s distinctive political economy in comparison to other Kurdish parts of Syria further east. She argues that the region’s proximity to Aleppo stoked economic developments and changes in property relations over the course of the 19th and early 20th centuries. This weakened the hold tribal elite held over society and giving the region a disposition for populist and eventually more explicitly left wing politics, partially explaining the PKK’s popularity in the region from the 1980s onward. Allsopp’s discussion of the Muroud is largely sourced from this Lescot manuscript.

The Muroud is also interesting in that it was very much of a time prior to nationalism becoming the hegemonic mode of politics in the post-Ottoman lands. Its participants were local Kurds but its politics were quite distinct from the contemporaneous Kurdish nationalist Xoybûn organization and the present nationalist parties derived from the KDPS and later from the PKK. The Muroud used and was used by Turkey as each sought to challenge French rule in Afrin and Syria more broadly.

PDFs of the book, entitled Le Kurd Dagh et le mouvement mouroud, can be found in the original French and in Kurdish on Kurdipedia. Below is an translation English I’ve produced mostly through Google Translate (I do not speak French) with some editing of my own. I’ve included the original footnotes and added some of my own, in addition to adding maps and photos and linking to other information regarding places and tribes mentioned. This post includes the introduction and a background section on the region and will be followed the rest of the booklet and its appendices in subsequent posts. In the future I hope to look into other available sources covering the Muroud

Brief guide to the Kurdish Hawar alphabet:

ê = ay/ei, î = ee, û = ou, c = j, ç = ch, ş = sh, x = Arabic letter khaa’, sometimes ghayn

ie. şêx = sheikh, axa = agha, hec = hajj

I. Introduction

The Kurd Dagh mountain range, which is connected to the Taurus system, is oriented from northeast to southeast; it is limited to the south by the Afrin valley. Only its southern extremity is located in Syrian territory.

The Syrian Kurd Dagh, or Jabal al-Akrad1, is between the valley of Karasu2 to the west; the plain of A‘zaz to the east; Afrin valley to the south; and the border which follows, to the north, a line going from Meydan Ikbis to Kilis. It is comprised of a series of parallel folds, of medium altitude (700 to 1200 m.), which delimit deep and narrow valleys, oriented from southwest to northeast, and between which it is rather difficult to travel. Only the Rajo-Afrin gap, which crosses the massif from west to east, offers a convenient access route; it is followed by the railway line.

Close to the sea and well-watered, the Kurd Dagh has many small torrential watercourses; the most important is that of Afrin river. The flora of the Jabal is that of the Mediterranean countries: a fairly dense scrubland covers the mountains; the valleys, warm and well sheltered, are suitable for growing cereals, vegetables and fruit trees.

The climate is very healthy; it is characterized by hot summers and winters with abundant rainfall and snowfall.

The Resources of Kurd Dagh

The main agricultural resources of Kurd Dagh are, in the valleys, wheat, barley, lentils, and until recent years, tobacco, the cultivation of which has recently been regulated by the administration. On the hillsides, the inhabitants plant fruit trees (olive trees3, pomegranates, apple trees, etc.) and vines4. The exploitation of the forest, today strictly monitored, used to produce large quantities of charcoal, which was exported to Aleppo. Livestock farming is also of considerable importance, particularly in the northwest portion of the mountain, which is not very suitable for agriculture. The livestock is mainly composed of goats and sheep, with cattle being less numerous.

Local crafts are virtually non-existent. However, in winter, women weave quite beautiful kilims in bright colors, which are generally used on site.

The Populating of Kurd Dagh

The region is entirely populated by Kurds - hence its name. Its inhabitants generally retain the physical and moral characteristics of their compatriots from the north; however, they have been strongly influenced by their Turkish and Arab neighbors; their customs, their costumes, their spirit are affected, as well as their dialect which, very corrupt, contains a large proportion of Turkish words and expressions.

The date of the arrival of the Kurds in Jabal is difficult to specify. However, it can be placed in an already ancient period: a chronicle of the 16th century, the Şerefname, quoting a certain ‘Mand’ who, at the beginning of the 13th century, received the Qusayr of Antioch as an appanage, adds that the Ezidis of the region, as well as "the Kurds of Cûm (middle valley of Afrin) and Kilis" rallied to this prince. We know nothing about the tribes who occupied the country at the time, but it is likely that the population of Kurd Dagh has changed profoundly since then. Indeed, all the current groups, apart from that of the Cûms, seem to be of recent settlement, and recall the regions from which they came: the region of Bîrecik, the Şikak, of Eastern Kurdistan (cf. the Shekakan of Lake Van); the Biyan are a branch of the Reşwan, (tribe residing in the South of Malatya); as for the Etmankan, they come from Dersim5, where a fraction of the same name still resides. The Ezidi community, too, has a majority of families from the most diverse tribes (Xalitan, Şerqiyan, Dawûdî, etc.) who took refuge in Syria during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Currently, five large tribes share the Kurd Dagh region. They are, to the south, the Cûm; to the east, the Şikak; to the west, the Amkan and the Şêxan; to the north, the Biyan. Detailed notices on each of them are provided in the appendix. The Ezidis, who once formed a very large minority and whose leaders played a leading role in local politics6, are today attached to the Cûm and the Şikak.

History of Kurd Dagh

The descendants of Mand, the first Emir of Kilis and Kurd Dagh, reigned without interruption until the conquest of Syria by Selim I. They were then deposed by the Sultan in favor of a Ezidi chief named Îzedîn. Power returned to them upon the accession of Suleiman the Magnificent7, Sheikh Îzedîn having died without leaving a successor. Ottoman centralization and court intrigues quickly put an end to the autonomy of the principality: in the 17th century, the last Emir was replaced by a governor, a Kurd, and originally from the Berwari tribe.

This dignitary is the ancestor of the Rûbari family that still exists today. His heirs, who occupied the citadel of Basoutah, worked to become independent in the Afrin valley. A century later, they were ousted from their stronghold by the Ganj (1150 AH, 1737/1738 AD). Following this victory, the newcomers, of Turkish origin, acquired predominance in the region. It was only around 1820 that the government was able to bring the Cûm back into the common rule, after having crushed the uprising of Battal agha Ganj (Kurdish: Betal Axayê Gênc).

The history of the tribes of the North of Kurd Dagh is made up of a long series of wars between Şêxan and Biyan. The Şikak and the Amkan, weaker, generally kept themselves away from these conflicts. The last one took place around 1850 and ended to the advantage of the Şêxan.

The period between this date and 1918 was not marked by any important event for the Jabal. The occupation of the region by the French was carried out without great difficulty, despite a few skirmishes. The Şikak submitted immediately, as did the Ezidis. The latter even provided partisans who contributed effectively to the penetration of the country. After some hesitation, Kor Reşîdê Biyan rallied to the new regime. The Şêxan and the Cûm followed his example in 1920. After a few years, during which bands equipped and supplied in Turkey maintained a fairly great insecurity, the Kurd Dagh found itself pacified. It remained calm until the first days of the Muroud agitation (1935-6).

II. Political and Social Physiognomy of Kurd Dagh

Political Structure of Kurd Dagh

The 19th century was marked, in Kurd Dagh as in the rest of Turkish Kurdistan, by profound political transformations. The strengthening of central power and the division of local autonomists had, as an immediate consequence, the ruin of traditional leaders and the advent of a new aristocracy of landowners. Of the old houses of Jabal, only those of the Ganj and the Rûbari retain a real influence. The others (Mala8 Hec Omerê, among the Biyan; Mala Caferê, among the Şêxan, etc.) are ruined or in decline. The main notables belong to families of recent importance, and enriched by land acquisitions (Mala Şêx Îsmayîl Zade, Mala Dîko, Mala Reş Axa, Mala Se'îdê Mamo, etc.). These new leaders draw their source not from the military strength of partisan groups, but from their own material prosperity; and this contributes to giving the Jabal a political aspect very different from that of other Kurdish societies.

One is struck by the extreme loosening of tribal ties in the societies of Kurd Dagh. Barely a century ago groups such as those of the Biyan and the Şêxan both retained enough cohesion and vitality to confront each other in wars. They are currently in full decline. No solidarity remains among the individuals who compose them. These have ceased to be "tribal people" and have become simple peasants, attached only to the fields they cultivate; they no longer consider themselves bound by any obligation towards their contributors or towards their leaders. Moreover, the notables of Jabal, landowners in perpetual conflicts of interest with their neighbors and their sharecroppers, cannot in any way compare themselves to the Kurdish feudal lords of the old school, who feel as many duties towards their men as they have rights over them. The so-called aghas of Kurd Dagh cannot count on the loyalty of their villagers; they have prestige only because of their wealth and are obeyed only on the lands that belong to them or that are mortgaged for their benefit.

The distribution of influences no longer respects, consequently, the frameworks that the division of the country into tribes formerly imposed. Thus, the Şêx Îsmayîl Zade claims to be the leader of the Biyan, but part of this group escapes his control, while several villages of the Şikak and Amkan, where they own property, find themselves placed directly under [Biyan] authority. On his side, Men'an Niyazi, nominal chief of the Şikak, no longer has much influence over his tribe, most of his properties being located around Azaz, in Arab country. Finally, besides the main aghas, the presence of a crowd of secondary notables fragments the territory of each grouping into so many small fiefs and causes innumerable rivalries to clash there.

If we add to the disappearance of the old tribal organization the fact that Kurdish national propaganda has never penetrated as far as the Jabal, and that everyone there remains ready to come to an understanding with the Turks as well as with the Arabs or the French, we will understand what magnificent terrain a region so politically divided offers to intrigues from outside, and we will better grasp certain aspects of the Muroud movement.

The Religious Question

It is a well-known fact that in Kurdish societies, religious leaders play a considerable political role. Until 1930, this was not the case in Kurd Dagh. The great brotherhoods were represented there by only a few followers: the Qadris had a sheikh in Meydanki9; a Rifaʽi sheikh, ‘Abd al-Rahman, from Bablout10, had about a hundred disciples; finally, a Naqshbandi from Damascus, Sheik Ahmed Lameh, periodically came to collect in the vicinity of Azaz.

Although deeply credulous, the Kurds of Kurd Dagh are not very religious: they conform only very irregularly to the obligations imposed by Islam (prayer, fasting, etc.), and there is probably no region in Syria where mosques are as few in number as in Jabal. The success of Muroudism was due to the social character of this movement, much more than to an explosion of fanaticism.

The Social Question

Property regime

As has already been indicated above, the agrarian regime in force in Kurd Dagh is that of large property. The most important estates are located in the Afrin valley, among the Şikak, and among the Biyan. On the territory of this last tribe, the Şêx Îsmayîl Zade family alone owns about twenty villages11. Among the Şêxan (especially in the North), and among the Amkan, the land is more fragmented, and one encounters a fairly large number of small peasant properties which, elsewhere, form the exception and tend to disappear in favor of the large and medium-sized owners.

The latter work in fact tirelessly to increase their estates. They have the easy part, because most of the small farmers who exploit their own assets, cannot produce the slightest written title; they often occupy their lands of recent date, and have rights on them only for having developed them. Nothing is easier for the ambitious agha enjoying political support than to have recognized by the courts or by the administration, the ownership of the coveted plot of land - and even that of the standing harvest.

Mortgages constitute an acquisition procedure just as practical, although more expensive: the agha makes an advance to the peasant at a generally very high rate (50% for 7 months). Most of the time, the debtor is unable to meet the deadline12. As the interests gradually capitalize, he soon finds himself forced to abandon his assets to his creditor.

Contracts

The most common form of contract is sharecropping: the owner provides the land and the seed, the net product of the harvest (that is to say, after deduction of the land tax and the expenses of the steward) is shared in half. The sharecropper must take from his share the interest on the cash advances granted to him by his master, he generally has barely enough left to ensure the subsistence of his family until the following season.

The Cûms, more influenced than the other tribes by Arab customs, also know the murabahah: the agha provides the field, and the seeds, as well as the harness and its food. A quarter of the net product of the harvest goes to the peasant.

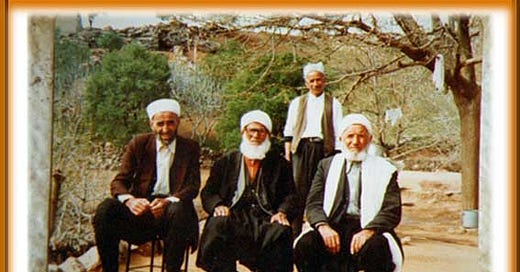

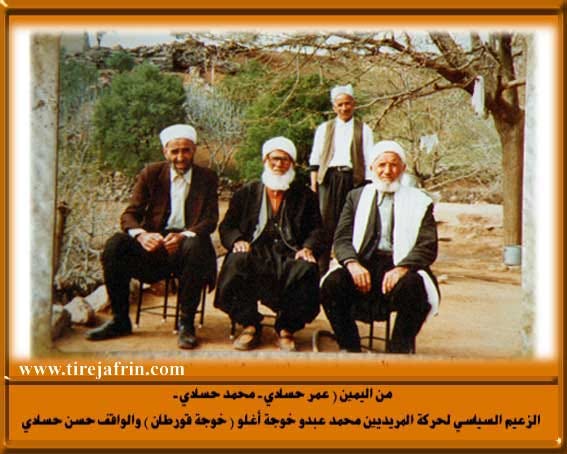

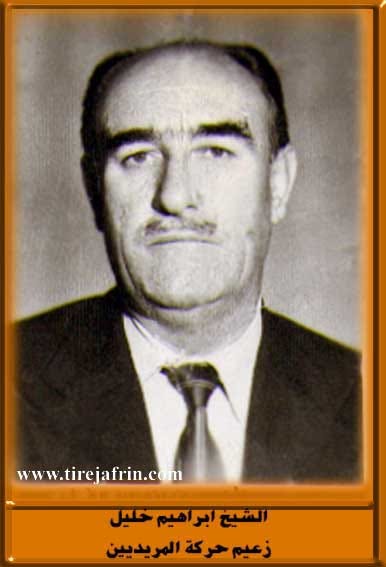

The country producing a quantity of olive seed, the oil presses provide their owners with considerable income. In fact, the operator collected 100 dirhams of oil from 4 rotols and 6 [unclear]; he also kept the oilcakes which, treated again, gave bitter oil. Good year bad year, a press brought in between I,000 and 2,000 L.S. It goes without saying that the aghas were the only ones to own such installations, and that they did not allow anyone to compete with them; the question of oil presses would take a considerable place in the economic demands of the Murouds. This rapid examination of the political and social situation in Kurd Dagh shows to what extent the country was prepared to serve as a theater for a movement like Muroudism. The incessant quarrels of the aghas, their lack of authority, the discontent of the peasants, all combined to facilitate the task of potential agitators. This is what Ibrahim Khalil understood.

Kurd Dagh (Tr), Çiyayê Kurmênc (Ku), Jabal al-Akrad (Ar) all roughly translate to ‘Mountain of the Kurds’ and in Syria refer to the region now commonly known as Afrin. Kurd Dagh is the most common name in historical documents due to Turkish being the administrative language of the Ottoman Empire. The name Afrin dates back to antiquity as the name of the river, but the city of Afrin is largely a product of the twentieth century.

Now commonly known as the Amik valley

Lescot: Between 1926 and 1939, 591,944 olive trees were planted.

Lescot: Kurd Dagh has 2,768,355 vines. The harvest is almost entirely processed on site into grapes.

Renamed Tunceli by the Turkish state after its 1938 military operation to crush a local Kurdish Alevi rebellion, commonly known as the Dersim massacre

Lescot: In the 17th century, their leader proposed to the French ambassador Nointel, passing through Aleppo, to ally himself with the King of France to wage war on the Turks.

Suleiman the Magnificent reigned from 1520-1566

Mala meaning house in Kurdish, here referring to prominent families

Lescot: Sheikh Is, whose son was killed by the Murouds in 1938.

Lescot: The only influential brotherhoods in Kurdistan are the Qadris and the Naqshbandis. The presence of Rifa'is in Kurd Dagh is due to the proximity of Aleppo, where this tariqa is flourishing.

Lescot: The extent of the domains of the principal notables of each tribe is specified in the Appendix.

Lescot: There are also cases of debtors who, having neglected to request receipts, were forced to pay the same debts several times.