Below are two excerpts from Swedish anthropologist Annika Rabo’s doctoral dissertation Change on the Euphrates: Villagers, townsmen and employees in northeast Syria (1986), which examines changing social relations in al-Raqqah city and its rural periphery during the economic transformations of the late 1970s. These excerpts offer an overview of al-Raqqah’s modern history. I’ve included the original footnotes from the excerpts, some images from the text, and left Rabo’s transliterations unchanged.

Chapter 1: Villagers, townsmen, employees

The expansion of Raqqa

The modern history of Raqqa began in the nineteenth century, when the town was in a pile of ruins after a long period of decay. In the 1880s a police-post was established in the vicinity; the Ottoman Government wanted to pacify the area for the benefit of traders, and the sheep-rearers of the region. Raqqa had links with 'Urfa in modern Turkey, whence the first civilian settlers came to Raqqa in the 1820s. To begin with, their migration was a seasonal one between Raqqa and 'Urfa; people kept sheep and moved between the two locations. As time passed some families stayed and in the 1880s started building houses using the materials available in the ruins. It is the descendants of these early arrivals who see themselves today as the 'real' Raqqa people. The early settlers spoke Arabic, but there were also Kurdish elements among them, as well as an Armenian family which had converted to Islam.

The main livelihood of these settlers was pastoralism and some cultivation. Not until the 1920s did settled life prevail in Raqqa and trade then became an important additional source of income. Some people with education began to act as functionaries for the government and many Raqqa men became valuable assets as regional intermediaries. Other migrants also came to Raqqa. A number of Circassians1 from Russia settled there in 1906 and 1917. In 1915 Armenians2 arrived after the infamous Turkish persecutions; it is still remembered how Armenians were hidden in Raqqa homes to save them from the Turkish authorities. Like the Circassians, most Armenians used Raqqa only as a stop-over, but a small number settled permanently and almost every sizable Raqqa family married one of its sons to an Armenian girl3. Since that period special bonds have been formed between the Christian Armenians of Raqqa and the native Muslim families.

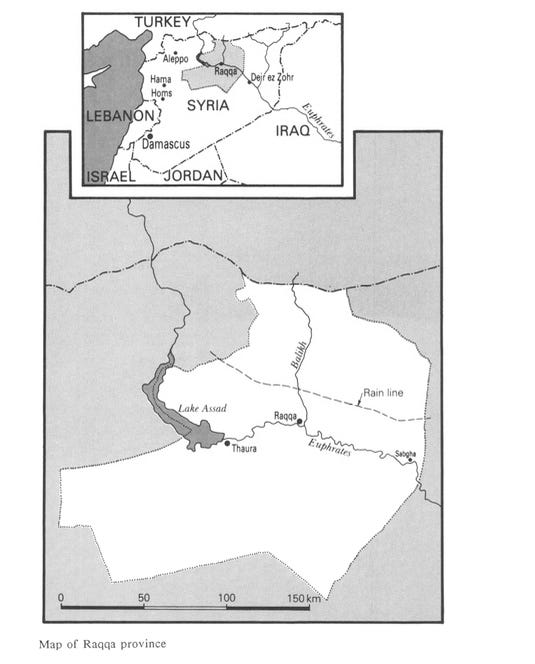

After World War I large semi-sedentary groups settled in the town and in the 1950s there was a new wave of immigration. People often migrated with their families from specific villages or regions because of drought or bad harvests, and these groups are even today referred to by their place of origin4. In 1961 Raqqa became the capital of a newly created province. Many employees were recruited from Deir ez-Zohr, Raqqa's Jeziira neighbour and the former provincial capital to which Raqqa was attached. The beginning of the Euphrates Scheme and the threat of flooding by the river in conjunction with the dam-building finally forced many villagers to move to Raqqa. The Euphrates Scheme has thus directly and indirectly given rise to a huge wave of migration. In 1930 Raqqa's population was estimated at 5,000. It rose to 15,000 in 1960, to 37,000 in 1970 and to perhaps 80,000 in 1980. In the last ten years Raqqa has grown more rapidly than any other town in Syria.

The creation of Raqqa province in 1961 and the establishment of the GADEB5 headquarters in Raqqa in the early 1970s brought not only new people to the town but also considerably improved communications. Until 1968 Raqqa had only a one-lane bridge connecting the town with the main Aleppo-Deir ez-Zohr highway. This bridge had been constructed by the British army in 1942 to carry military materials6, but in 1964 the construction of a new bridge began. Between 1966 and 1969 the length of tarred roads in the province increased from 9 km to 76 km. Electricity had arrived in Raqqa town in 1948 and running water in 1950, but a sewerage system was installed only in 1962. Television arrived in 1973, and by then work on the new highway between Raqqa and Aleppo had begun.

With the establishment of Raqqa province the town itself became subject to a certain amount of planning and a provincial administrative center was built. This mujamma' contains the offices of the whole provincial administration and is situated to the north of the souq and the old quarters of the native townsmen. The same section of the town also contains the Peasants' Union, the Teachers' Union, the Ba'th party building, a government hospital built in the 1970s and several schools. There are also apartment houses for the employees who arrived with the expansion of the province. A very elegant residential quarter with fashionable villas is springing up; this is where the governor's residence is to be found. Next to this fashionable quarter is a more modest residential area where there is tremendous building activity. Many of the houses here are inhabited by newcomers to the town, but a number of native townsmen also live here, since the natural limits on expansion in the city center have forced people to move out.

North of this administrative/residential area the environs of Raqqa spread in a crescent to the north-east. On the eastern edge in the Sabgha direction, we find the industrial market and workshops for agricultural machinery and vehicles. Here are blacksmiths and small repair shops. At the opposite end of town the Euphrates Scheme administration (GADEB) is situated. Between and beyond these two fringes Raqqa has a strip of semi-legal squatter quarters. There is also a railway station, a big sheep-market and a modern silo, an ultra-modern sugar factory, and a factory for pre-fabricated cement pipes administered by GADEB. The adjacent villages on the fringes have almost spread into the town.

Chapter 2: Scheme, state and party

When powerholders speak of the future of Raqqa province they often mention its history. Through the Euphrates Scheme, the Syrian state of today hopes to revive the ancient glory of the province, which was part of Mesopotamia, and was important and rich during the Assyrian and Babylonian civilizations and up to the peak of the Arab Islamic era. Modern Raqqa is built on and from the ruins of earlier civilizations. Today there are few visible remnants of these glories, but some fragments remain from the eighth and ninth centuries when Raqqa was an important town in the Abbasid Empire. There were impressive waterworks and a brick wall surrounded the whole town. One could travel from Raqqa to Baghdad shaded by trees the whole way. Today there are hardly even shrubs. With the political conflicts and the economic decline of the Islamic empire this region also suffered. Raqqa was destroyed and sacked by Tamerlane in 1371. By the end of the fourteenth century the Jeziira was no longer a rich and densely populated agricultural region. For the next 600 years the destiny of the province fluctuated with the ups and downs of the empires controlling it. At times of stability, agriculture and trade expanded and the population increased; at times of instability the reverse process took place7.

When the Ottoman authorities established the police-post in Raqqa it was part of a policy to resettle peasants east of Aleppo. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries powerful beduin tribes migrated from the Nedj in the Arabian peninsula to the Jeziira of today's Syria and Iraq8. In an effort to break the power of these tribes the authorities tried to incorporate them into the power structure of the empire. It was hoped that this would also provide stability for the non-beduin groups living along the banks of the Euphrates. These groups, now called the shawai'a9, were shepherds pursuing a little supplementary subsistence agriculture, and they were politically dominated by the beduin. Western historical accounts often ignore the shawai'a as they were of no political significance, nor were they romantic in the eyes of the Western traveller. Thus Lady Ann Blunt (1897), writing about a trip in northern Syria and Iraq in the 1870s, devotes many pages to the different beduin tribes. She writes about their origins and inter-relations, but she has little to say about the peaceful groups who were subject to them.

The last remnants of the Ottoman empire fell apart after World War I and the Middle East was split, against the will of the Arabs, into mandated territories administered by the victorious allies10. Syria became a French mandated territory and was further split into 'states"11. The Jeziira was directly ruled by the French and its administrative center was at Deir ez-Zohr, a small town about 120 km east of Raqqa. The French were determined to pacify the region, but it took them some time even to establish nominal supremacy12. They continued the reformist policies of the late Ottoman empire13. Land registration was in the forefront of these reforms. Huge tracts of land had been registered in the name of tribal sheikhs, both among the beduin and non-beduin groups in order to bind them to the powerholders. Many people were afraid to have legal leases in their own name as this could force them into the Ottoman army; instead they let their land be registered in the sheikhs' names. The French continued to register land on behalf of the sheikhs. They also played important beduin tribes off against each other. To the subjugated groups along the Euphrates, French rule did bring advantages, however. Earlier they appear not to have formed coherent units; they most probably have varied origins and no tribal confederation existed among them. A French commander working in the Jeziira in the 1930s noted their many divisions, and claimed that it was impossible to verify the development of the various groups historically. He found each group putting forward different versions of its origins. The shawai'a tribes themselves are usually not genealogically minded. The internal stability during the French mandate nevertheless made it possible for the shawai'a tribes to weld themselves into specific and distinct groups for the first time. In a sense these tribes were created during this period.

The mandate was not popular among the Syrians, and revolts. broke out in different parts of the country. The French finally abolished the hated state system, and Syria was forged into one unit in 1941 when independence was formally recognized.

Full political independence was won in 1946 when the last French troops left the country. It was then open to traditional city elites to seize power and rule in harmony with the big landowners. This state of affairs perpetuated the well-known exploitative relations between the city and the countryside and underlined the weak position of many religious minorities.

At independence the Jeziira was only marginally incorporated into the political and economic life of the nation. The introduction of cotton changed this situation. The crop was grown in other parts of Syria, and introduced by urban traders to the Jeziira in the late 1940s. Land was under-utilized in the region. The period of the mandate had made no dramatic impact on regional economic life. The French had made no effort to start any kind of economic development. In the steppe zone the beduin lived off camels, sheep-rearing, agriculture and tribute, and powerful sheikhs levied taxes on agricultural villages. In Raqqa the native townsmen continued with trade, administration and agriculture mixed with sheep-rearing. Along the river banks the shawai'a tribes cultivated subsistence crops and herded their sheep on the steppe. More land was registered in the name of shawai'a tribal sheikhs than anyone cared to utilize. Clearing the land was difficult along the river where thorny bushes and brambles grew in abundance. Then urban traders, mainly from Aleppo, came to the Jeziira and rented land. They hired labour - often from their own region -, cleared the land, installed diesel pumps and began to cultivate cotton. The Korean war created a great demand for cotton, and world market prices soared. In just a few years cotton became the most important crop along the river banks.

The pumps revolutionized the agriculture of the Euphrates and at the same time tractors were introduced into the plains of the Jeziira steppe. Urban traders leased huge tracts of land from tribal leaders to cultivate wheat and barley. The harvests in the early 1950s were immense; rains were plentiful and the soil was rich after a long fallow period. Fortunes were amassed on irrigated cotton and rainfed wheat cultivation. Most of this wealth left the region since the traders renting the land and running the agro businesses had little interest in long-term development policies and the government did not interfere. The tribal leaders often used their share of the profits for conspicuous consumption, and the locally employed agricultural labourers only earned enough for their subsistence. In the mid-1950s the Syrian government woke up to the inherent conflict over land titles in the steppe. The Tribal Law, which had made the beduin administratively autonomous was then abolished, and the beduin were put on equal legal footing with all other Syrian citizens. Tractorized agriculture in the steppe had already changed the traditional basis of the beduin economy. Only the sheikhs had become rich by renting out land, but the group as a whole was weaker both politically and economically. There was now a shift in power towards the shawai'a. Their tribal leaders became "cotton sheikhs" and acquired enormous wealth, which strengthened the whole group vis à vis other groups in the region. But relations between the shawai'a sheikhs and their fellow tribesmen changed drastically. Shawai'a without land titles often became wage labourers on the large farms of their own kinsmen. Sedentarization among this group of people also took place quickly. Villages were built and sheep-rearing became secondary to work with irrigated cotton.

The 1950s in this way brought totally new economic forces into the Jeziira. The region became part of the world market, and emerged as economically very important to Syria. Outsiders also moved into the region on a more permanent basis to profit from the new opportunities. Urban traders from outside the region became muzara'iin - 'farmers' - using land, labour and water.

On the national scene the economic advances of the 1950s brought out many conflicts. A pan-Arabic movement with a progressive program gained ground among the masses as one government after another failed to bring either equality or justice to the majority. Syria was very much involved in the conflict over Palestine, and international and pan-Arab issues deeply influenced Syrian internal politics. Radical forces were able to forge a union with Egypt in 1958, which was seen as a victory over American influence in the region14. The union failed to achieve the changes many radicals had hoped for, however; it soon became very unpopular with the urban masses, and was dissolved in a coup d'etat in Damascus in 1961. After two years of instability the Ba'th party took power following another military coup, and since 1963 this party has controlled the state apparatus. The union, though nowadays often regarded as a failure, nevertheless instigated important changes. A land reform was planned and expropriation began, but internal political fluctuations made implementation slow. It was also during this period, that the first plans for the Euphrates Scheme were formulated. When the Ba'th party took over power, its base was weak and the government needed allies to push through its reforms. The Land Reform Law was amended and re-amended depending on the political situation15. Finally in the mid-1960s it was implemented in earnest.

In Raqqa province the land reform drastically curtailed the holdings of the shawai'a tribal sheikhs, but still left them as large landowners compared to the average tribesman. The use of state land in the steppe was regulated16. Land redistributed in the reform was seen as distinct from ordinary private holdings. The beneficiaries were to organize peasant cooperatives, and the land could not be leased to the urban farmers, nor sold. One objective of the reform in the Jeziira was to curtail the power of the urban farmers. But since the beneficiaries had few means to implement the co-operatives these failed to a great extent in the Jeziira. The new Peasant Union, however, gradually became a powerful institution under the direction of the Ba'th party. Instead of the sheikh and the urban farmer, the party leaders and the Peasant Union employees became essential mediators and brokers between the peasant and the market. Wheat and cotton were no longer sold on a 'free' market but became crops controlled by the state. The rural population in Raqqa province had hardly adjusted to these new conditions when the early 1970s brought a fresh major development; the Euphrates Scheme.

Circassians from the Black Sea area were urged by the Ottoman authorities to come and join their co-religionists in the Middle East. In Syria the group consists of Tjerkes and Daghestanis. Many passed through Raqqa because of religious persecution in Russia. There is still a small Circassian community in Raqqa, but the largest Syrian community lived in Quneitra before the Israeli occupation of the town in the war of 1973.

Armenians have lived in Syria continuously for centuries, but not until the Ottoman massacres did mass migration take place. Today Armenians constitute the largest non-Arab Christian group in Syria.

I’m not sure what Rabo’s sources are for this claim and whether it refers to consensual marriages or Armenian women abducted and sold into slavery or forcibly assimilated into Muslim households during the Armenian Genocide.

The semi-tribal group from which many members settled in Raqqa came from the Deir-ez- Zohr region. People from Sukhne, between Raqqa and Palmyra, came to Raqqa quite early on, often after working as traders in Aleppo. Another group from Ta'if in central Syria arrived in the 1950s and they now control the vegetable market. In the early 1950s many also came from Hauran, close to the Jordanian border. This area was severely hit by drought, forcing much of the population to migrate.

Earlier footnote: GADEB: The General Administration for the Development of the Euphrates Basin.

During the latter part of World War II the British army more or less controlled northern Syria. The Euphrates river had to be crossed to send war-materials to the eastern front. The British brought Gurkha soldiers with them and also employed local labor to construct the bridge. Some say they paid handsome wages and in general behaved better than the French mandatory power.

The relation between political stability, density of population, expansion of trade and agriculture is of course exceedingly complex.

It is possible that the beduin movements of the 'Aniza and Shammar tribal confederations from the Arabian peninsula into today's Iraq and Syria, as well as the conflicts between them, were caused by lack of pastures. The beduin pushed north for about 150 years.

Shawai’a, the plural form of Shāwi. From earlier in the text: “The shawai'a are thought of as sheep-rearers but the term connotes a whole range of derogations. Shawai'a are uncivilized, uneducated country bumpkins with a narrow parochial outlook, and tied to the bonds of tribalism; they are, according to the outsiders' perception, not proud and free like the beduin, but weak and dominated.” Earlier footnote: Shawai'a probably originates from the word sha'a sheep. In southern Syria the word is used without derogatory connotations for all non-settled sheep-rearers. In most Syrian regions the word is not known; people who have never visited the Jeziira call the shawai'a, "Arab" or "beduin."

The mandates were the outcome of secret Franco-British negotiations during the First World War. The British were supporting the Arab revolt against the Ottoman government. At the same time, with the French, they were planning the division of the region. Britain also put forward the Balfour declaration in which they looked with favour upon "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people". At the Versailles conference of 1919 France and Britain were able to overrule Arab national aspirations and at the San Remo conference the division of the region was carried through. France was to administer today's Syria and Lebanon, and Britain was given the mandate over Palestine, Transjordan and Iraq. Unrest broke out in various parts of the Middle East and in 1920 an independent kingdom of Greater Syria was proclaimed in Damascus, but the revolt was crushed.

France began its career as a mandatory power by separating Lebanon from Syria and enlarging the traditional Lebanese administrative borders. What was left of Syria was split into the Government of Latakia, the State of Jebal ed-Druze, the Government of Damascus and Aleppo (later united into the state of Syria), and the Sanjaq of Alexandretta, which was handed over in 1939 to Turkey. The Jeziira was separated from the other Syrian 'states' and ruled directly by France.

In the Raqqa region, Hatchem, sheikh of the Feddan beduin tribe, refused to recognize the rule of the French and instead created a 'state' of his own in 1920. He received support and help from the local population and from the Turkish authorities. Even taxes were collected in this 'state'. But after fifteen months Hatchem's state fell. By then the French had acquired the support of Hatchem's cousin Mujhim who became the Emir of the Feddan.

The modernizing reforms of the Ottoman government between 1839 and 1856 (the tanzimaat) sought to increase the central authority. The Beduin were for a time subjugated and local pashas were stripped of power. The reforms tried to do away with taxfarming (iltizam) whereby the peasants were actually robbed, and instead the government tried to build up a central tax system. In 1858 the Land Code was passed with the intention of registering land on behalf of the peasants who tilled it.

The Americans had been trying since the early 1950s to persuade the Arab states to join an anti-Soviet defense alliance. Iraq signed an agreement in 1954; later Turkey. Iran and Pakistan also joined. But massive anti-government demonstrations took place in Iraq. Jordan was also shaken, as well as Lebanon when people feared these countries would also join the Baghdad pact. Only Egypt, led by president Nasser, and Syria, which had a strong communist party, held firm against the pact. In 1957 US troops aided king Hussein of Jordan against the leftist movement and in 1958 the Americans landed troops in Lebanon in response to president Cham'oun's call for help in the on-going civil war. The whole Middle East was in a state of turmoil, but the Iraqi revolution of 1958 put an end to the pact.

The Land Reform Law originally limited ownership to a maximum of 80 ha of irrigated land. and 300 ha of non-irrigated, plus provisions for dependents. Before the reform only 0.6% of the rural population owned 35% of the land. 1.3 million ha were expropriated but less than 5% of this was distributed initially. After the union with Egypt was dissolved in 1961 the former landlords lobbied parliament for better compensation for land expropriations as well as higher ceilings of ownership. But a coup in 1962 prevented this turnabout from being realized. Land was also redistributed at a quicker rate. After an internal Ba'th coup in 1966 amendments were made for land turned from non-irrigated to irrigated in order to stimulate agricultural investments. By 1971 85% of the expropriated land had been redistributed. Land reform in Syria has been quite peaceful but rather limited. The landlords are still left with large land holdings and the richer peasants have been better able to profit from loans and investment opportunities. The co-operatives, formed for beneficiaries of the land reform, have also had great difficulties with credit and marketing.

The Islamic concept of land tenure gave the state the ultimate ownership of all land (miri) except lots in towns with property built on them (mulk) and land tied to religious purposes (waqf). In the fourteenth century the central power began to pay for state offices by distributing land. The land title still belonged to the state, and the office-holders were responsible for the control of the peasants. By the sixteenth century this system was disintegrating. The state needed money and accepted the growing power of tax collectors who often replaced the real office-holders in the control of the peasant surplus. Finally the land-offices were abolished by the Ottoman sultan Mahmoud II in 1831 and the land was to be directly administered by the state. This was the beginning of the tanzimat. In the Land Code of 1858 land was divided into five categories: mulk private property, miri (amlak duala) state land, waqf - religious foundations, matruk public and mayit dead land. Miri was often in practice converted to private property as it was leased to the user, and could be 'inherited' and fragmented. Large landed estates often originated with the tanzimat reform, and thus the purpose of the Land Code largely failed. "The various forms of evidence used by individuals to claim title to land and register them in their own names, and the poor states of the registers, and the fear that registration might lead to conscription could be cited as some of the major technical causes of the failure of the Land Code. Unscrupulous individuals appear to have taken full advantage of this situation to amass land often to the detriment of their fellow citizen and in open conflict with government officials."