Wrath of the Olives: Tracking the Afrin Insurgency Through Social Media

originally published on bellingcat.com

Concluding in late March 2018, Operation Olive Branch resulted in the capture of Kurdish-populated Afrin district of Aleppo by the Turkish Armed Forces (TSK) and allied Free Syrian Army (TFSA) factions. The bulk of Afrin’s YPG and YPJ defenders and over a hundred thousand of its inhabitants fled east to the nearby Shahba region during the final week of the offensive. Since then, the district has been governed by a mosaic of Turkish-backed civilian institutions and a diverse host of rebel factions prone to infighting. This fractured security situation has led to widespread allegations of theft, human rights abuses, destruction of cultural sites, and wholesale demographic changes being implemented by Turkey.

Please note that some of the media featured below can be considered disturbing.

Within this environment, the YPG, alongside what appear to be multiple front groups, have been conducting an ongoing ten-month long insurgency. These factions have used a combination of tactics including IED attacks, roadside ambushes, kidnappings and executions broadcast to internal and external audiences through social media to disrupt Turkish-backed rule while signalling their tenacity and reach.

Before Operation Olive Branch, Afrin mostly avoided the brutality and destruction large swaths of Syria have suffered in the past eight years. Regime forces withdrew soon after the beginning of the Syrian uprising, leaving the region to the Kurdish ‘Democratic Union Party’ (PYD) and its affiliated YPG and YPJ militias. Since then, a de facto nonaggression pact with the regime allowed the district to avoid indiscriminate bombardment that has ravaged rebel-controlled Syria.

This relative calm attracted internally displaced persons (IDPs), with some estimates numbering as high as 100,000. However, the lack of recently constructed housing infrastructure visible on satellite imagery points to sizeable numbers of original inhabitants and IDPs leaving for Turkey and beyond during this period. The population of pre-war Afrin, home to 172,000 people according to the 2004 census, was overwhelmingly Sunni Kurdish, with small geographically-confined Yezidi, Protestant Christian, and Sunni Arab populations.

Fighting between the YPG and nearby rebel groups broke out in Spring 2016, as fighters from Afrin took advantage of a regime offensive to seize a number of northern Aleppo locations within the Shahba region. It was during this 2015-2016 period, coinciding with the breakdown in domestic peace talks with the PKK and the rapid expansion of the PKK-linked YPG at the expense of the Islamic State, that Turkish priorities in Syria changed. A shift occurred from materially supporting the rebels with the goal of regime change to direct intervention in northern Aleppo, assumably in an attempt to block and reverse the YPG.

Tracking contemporary events in Afrin is complicated by the district’s chaotic security conditions since March, and the understandably highly polarised local media reporting on it.

While this study focuses on attacks declared by three anti-TFSA groups, there have been numerous instances of shootings and bombings in Afrin that have gone unclaimed. Whether such attacks were committed by the insurgents, related to the many cases of rebel infighting, or were products of Idlib-based assassination campaigns is hard to discern.

The three organisations I focus on here are the YPG itself, Ghadab al-Zaytoun (GaZ) or Wrath of Olives, and Hêzên Rizgariya Efrînê (HRE) or Afrin Liberation Forces. At least three other anti-TFSA groups announced themselves in this period. However, these groups only claimed a handful of attacks including bombings of public places that caused civilian casualties. They have faced allegations of being manufactured social media phenomena or an MIT false flag by PYD supporters and were public disavowed by the YPG.

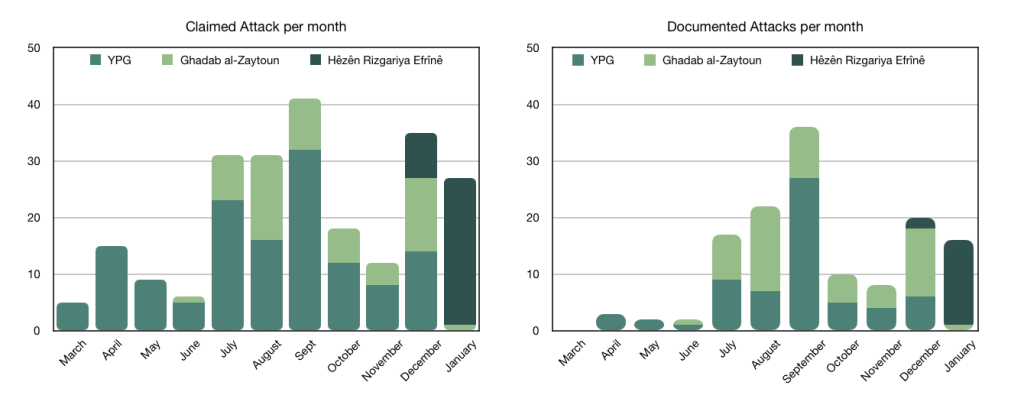

Cumulatively, the YPG, GaZ and HRE have claimed responsibility for almost 220 attacks between late March 2018 and the end of January 2019. Approximately half of these occurred between July and September, representing the high point of insurgent activity.

Several characteristics of each group’s activities differentiate them from each other. The YPG campaign, which has only partially been documented with visual evidence, has occurred entirely within the borders of the Afrin district and has been dormant since mid-December.

Ghadab al-Zaytoun, a group whose existence was announced in June 2018, has operated throughout Afrin and the rest of TFSA-controlled northern Aleppo (commonly referred to as the Euphrates Shield territory). They have announced attacks in Idlib as well — yet the veracity of such claims is unclear. GaZ gained notoriety for their highly controversial kidnappings and executions of TFSA members and suspected collaborators, a grim hallmark that has differentiated their actions from official YPG activity in Afrin.

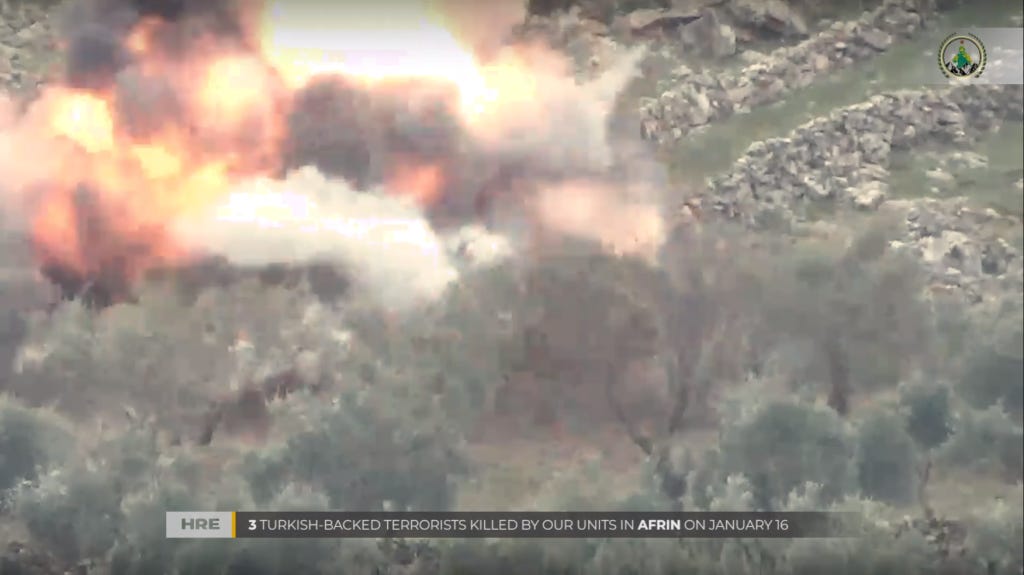

Hêzên Rizgariya Efrînê, or the Afrin Liberation Forces, is the most recently created of these insurgent groups. Its existence was declared in mid-December 2018 and interestingly coincided with the ceasing of YPG attacks and a dramatic decline of Ghadab al-Zaytoun’s. Unlike the others, HRE frequently utilises Anti-Tank Guided Missiles (ATGM) in its attacks on opposition targets, launching these from the PYD-controlled Shahba region. Despite the inactivity of the YPG and GaZ, HRE’s 33 attacks since December 18 have made the last two months of the insurgency the most dynamic since summer.

It is speculated that Ghadab al-Zaytoun and Hêzên Rizgariya Efrînê are merely front groups for the YPG. This assumption is based on the similarities they share in terms of area of operations, tactics, and rhetoric. Referenced as a precedent is the understanding of the relation between the Kurdistan Freedom Hawks (TAK) and PKK in Turkey, in which the former is seen as a front for the latter and is often used to target civilians while providing the PKK with plausible deniability.

While Ghadab al-Zaytoun’s actions have almost entirely targeted militants, its publishing of execution videos is a behaviour the YPG would assumedly wish to avoid association with. Similarities in tactics and geography give the “front group” theory credence as well. However, a definitive answer to the issue is currently not possible due to lack of information on leadership and members. This study approaches the YPG, GaZ, and HRE as separate groups, or brands, in order to examine both similarities and differences in their activities.

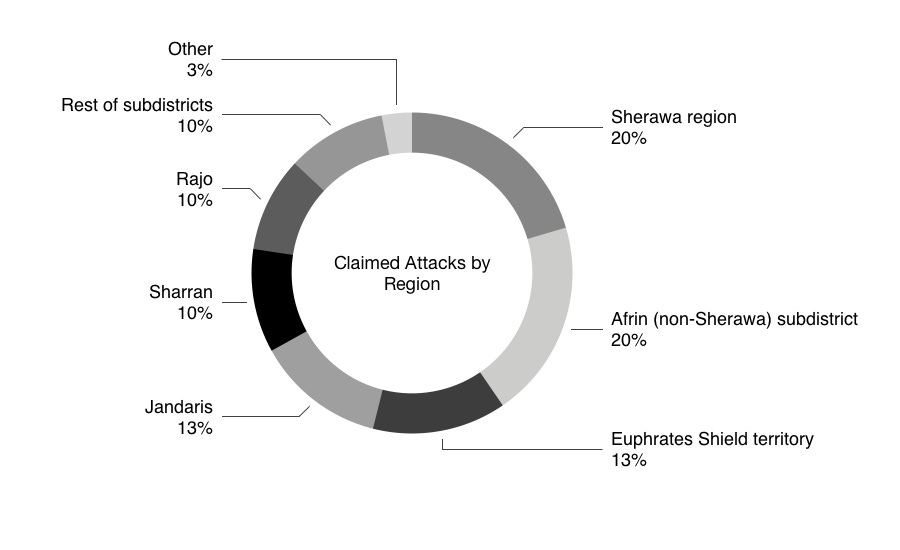

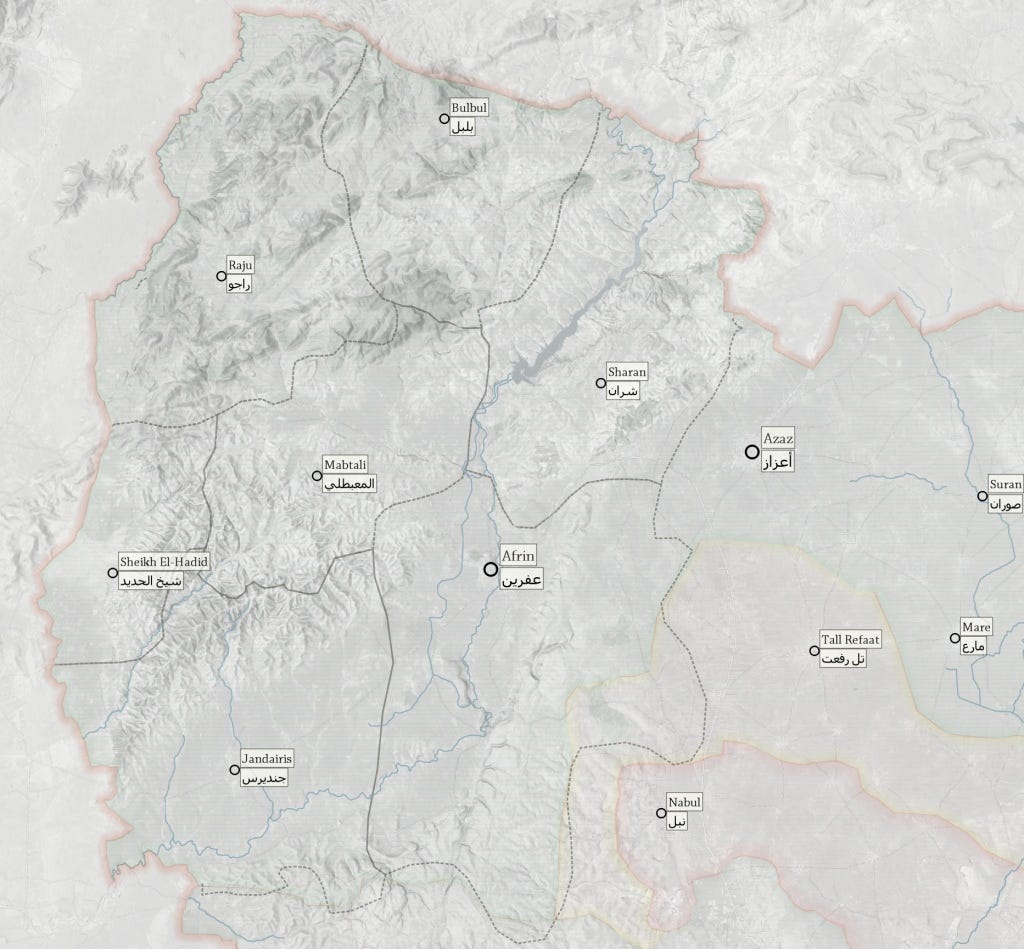

Besides a central valley which hosts the Afrin river, the region’s geography is hilly and littered with olive plantations. Afrin is divided into seven subdistricts, the three largest by population being Afrin, Jandaris, and Rajo. The district’s southeastern corner, a rocky extension of Aleppo’s Jebel al-Simeon region, is known to by locals as Sherawa. It should be noted that multiple spellings of place names are common, not just when transliterated from Arabic spelling to English, but between the Kurmanji dialect of Kurdish and Arabic as well. Some towns have different names in Kurdish and Arabic, due to the regime’s Arabization campaign during the 1970s.

As the only one adjacent to the PYD-controlled Shahba region, the Afrin subdistrict has witnessed a plurality of total insurgent activity since March. A majority of these claimed attacks have occurred within the Sherawa region, pointing to a high frequency of insurgent infiltration from Shahba. While HRE and the YPG have maintained high levels of activity in Sherawa, 38% and 22% of total claimed attacks respectively, Ghadab al-Zaytoun has mainly operated around Jandaris, Rajo, and uniquely throughout “Euphrates Shield.”

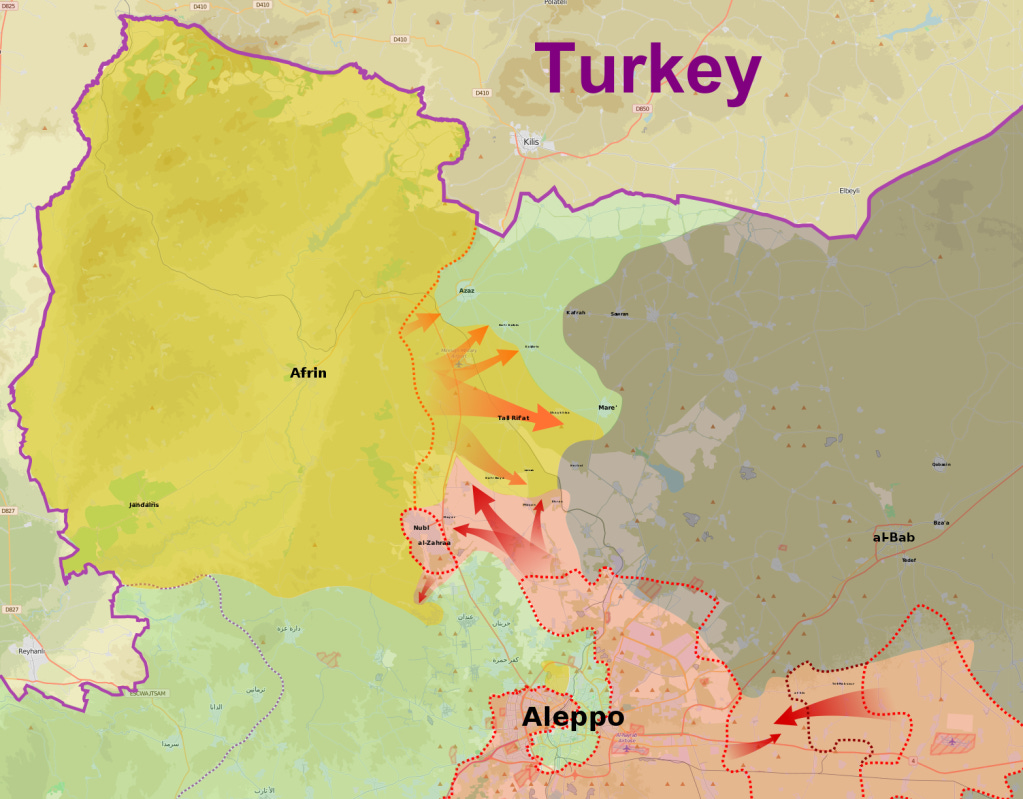

Since the beginning of December 2018, the geography of the insurgency has shifted east, further highlighting the importance of Sherawa. Whereas the Afrin subdistrict and Euphrates Shield territory make up the location of 53% of total claimed activity, during December and January this percentage has gone up to 70%. However, the nearly 20% rise in incidents within the ES region is not due to a rise in Ghadab al-Zaytoun’s ambush and execution attacks behind enemy lines. Instead, it is due to the rise of HRE, particularly their use of ATGMs across the Shahba-ES frontlines.

The most common tactics used by insurgents in Afrin have been roadside ambushes and IEDs, making up just under half of all claimed incidents. The YPG, Ghadab al-Zaytoun and Hêzên Rizgariya Efrînê have frequently utilised these methods, with no recognisable difference in technique or geographical pattern between them:

Devices are also attached to cars and motorcycles parked next to static targets, such as the recent Ghadab al-Zaytoun attack in Afrin city on 2/21/19. This type of attack is less frequently recorded than others, but in many instances such claims are corroborated by reports in pro-rebel media.

Opposition groups in the area frequently find and disarm such devices, publishing images of them to social media accounts. Materials used to manufacture IEDs have also been discovered in what appear to be YPG weapons caches.

While many of these IED attacks occur during the day, roadside ambushes predominantly occur at night. These feature one or two gunmen equipped with small arms, occasionally furnished with a silencer. A cameraman is typically present to document the attack, and the gunmen wear head-mounted cameras as well.

The insurgents attempt to shoot the driver and occupants at a distance, stopping the car before rapidly approaching, filming the victims and frequently removing their bodies from the vehicle. An insurgent will occasionally remove the victim’s wallet in order to display their identification card. Videos frequently begin and end with a piece of paper featuring the date and location of the attack shown to the camera for authentication.

From what can be seen of the small arms used in these attacks it appears that they are of standard make and model found in Syria. However, a closer examination of this aspect by an expert on the topic could potentially glean patterns within or throughout the three different groups. It is currently unknown whether the insurgency is equipped by stocks in the Shahba region, from SDF territory in Manbij and brought over regime lines, or directly by members of the regime itself.

Examinations of the attire worn by the guerillas are equally inconclusive. In a September YPG video shot deep in northern Afrin, the militant (above) can be seen wearing a MARPAT fatigue commonly used by the YPG, while in an August video filmed in Euphrates Shield territory the Ghadab al-Zaytoun gunman is in all-black civilian attire. It is unclear whether these differences are due to the location of the attacks, or insurgent branding, and the low visibility of most such videos make the study of such patterns difficult.

Through rebel media we have several images showing both what insurgents killed in Afrin have carried on their persons, as well as what hidden weapons caches in the area contain. The first image was taken in the Sherawa region in early October and presumably depicted what insurgents infiltrating from Shahba carried: Extra magazines and ammunition, grenades, video and surveillance equipment, phones, batteries, canned food, and tobacco. The image of the weapons cache, discovered a month prior, shows many of the same items, as well as what appears to be supplies for making explosive devices.

The Afrin insurgency has gained the most notoriety for the production of execution videos. Of the three, groups covered here only Ghadab al-Zaytoun has engaged in this manner. Executions make up 27% of GaZ’s claimed attacks, constituting seven per cent of declared insurgent activity overall.

The first of these videos was published on August 5, portraying the execution of a civilian named Akash Haji Ahmed. GaZ identities him as a member of the recently created Sharran Local Council, a Turkish-supported governance body representing one of Afrin’s subdistricts. The accompanying text accuses the local of serving “as a guide” to Turkish-backed forces, assisting in “the abduction of dozens of civilians from Afrin…fate unknown,” as well as sending threatening letters to Afrin natives who fled in late March, warning them not to “return to their homes.” While riding a motorcycle, Akash is stopped by masked men, manning a faux rebel checkpoint. He is then forced to dismount his bike, runs into the woods, and is subsequently shot in the chest.

Since this video, fifteen other GaZ executions have taken place. Two victims, Ahmad Zakaria al-Muhammad and Muhannad Zeer, were reportedly civilians accused of being informants for Turkish authorities. The rest have allegedly been members of various Turkish-backed opposition groups, who were kidnapped in Afrin or elsewhere before being interrogated and executed. Ghadab al-Zaytoun also claimed to have “assassinated” two members of the so-called Free Police, another Turkish-supported governance institution, however, It is unclear whether they were kidnapped as well as only pictures of their corpses were published.

The use of Anti-Tank Guided Missiles (ATGMs) in guerilla attacks on the TFSA is a recent phenomenon. In its defence of Afrin during Operation Olive Branch, the YPG media centre published as many as sixty videos of such missiles being used. However, ATGM usage in the district was not documented again until a November 26, 2018 attack targeting a white truck near the Sherawa town of Bassouta. Since then, the YPG launched two more, also in the Sherawa region. One of these, targeting a vehicle in the town of Kimare on December 13, 2018, corresponds with the reported death of a Turkish soldier in the area.

Since its formation in mid-December, Hêzên Rizgariya Efrînê has documented itself launching six ATGMs. Four of these, fired from the Shahba region, target vehicles and positions within Euphrates Shield territory. While none of the ATGM videos show the launcher used, It is quite likely that the majority are Russian-produced and from regime stockpiles, either sold or given to the YPG in Afrin by the regime or captured and then sold by rebels over the years.

It is unclear whether this new tactic is due to rising tensions with Turkey over the future of Manbij and areas east of the Euphrates or perhaps a perceived Turkish success in limiting the geographic reach of the insurgency inside Afrin during the months of October and November. However, it does correspond with a recent uptick in skirmishes between YPG forces in the Shahba region and TFSA groups around the town of Mare.

An examination of these three groups’ social media presence sheds some light on their intended audiences. The YPG and Hêzên Rizgariya Efrînê’s associated Twitter accounts (@DefenseUnits, @HRE_official) are operated in English, as are the captions in the majority of their videos. When the two groups put out their press releases, they are similarly formatted and published as separate documents in English, Arabic, Kurmanji (Kurdish), and Turkish. It appears that the YPG and HRE intend to gain attention amongst a Western, English-speaking audience active on Twitter.

This stands in contrast to how Ghadab al-Zaytoun operates on social media. GaZ’s website and the videos published on it are entirely in Arabic. News of recent operations are announced alongside diatribes attacking Turkey, the TFSA, and collaborators while highlighting the justness of their cause. This points to Ghadab al-Zaytoun targeting an audience inside Afrin, both of their supporters and their enemies. The macabre music and imagery of their videos appear as an attempt to intimidate enemy combatants and potential informers.

Assessing the casualties afflicted by and on the insurgents in Afrin is quite challenging due to the previously mentioned opaqueness of information in the region and the only incomplete documentation of claimed guerrilla activity. Turkey and the local opposition groups have a vested interest in downplaying the ability and effectiveness of the insurgency, while it appears the YPG have inflated their successes.

Several Turkish soldiers have been killed in Afrin since March of 2018. The YPG have claimed responsibility in such instances, however the Turkish government has often attributed cause of deaths to demining operations. The number of rebel fighters reported as “martyrs” by their respective factions is in the dozens, while the YPG claims are astronomical. As there have been over a hundred attacks with visual evidence, including numerous dead bodies (at least 48 by October), as well as countless unclaimed bombings and shootings, it seems a prudent estimate would place opposition members killed at over a hundred at least, with dozens of vehicles damaged or destroyed.

The YPG Press Office has announced 44 “martyrs” who were killed within Afrin or on its borders since March 18th. Of these, 28 died in the following three weeks, while fighting was still going on in Sherawa and in Afrin’s isolated, forested central highlands not entirely controlled by TFSA factions at the time.

Discounting these from the insurgency total leaves sixteen confirmed dead, a remarkably low level of casualties for ten months of activity. Many of the “martyrdom” notices are corroborated by Turkish and rebel reports of counterinsurgency operations or border clashes, often accompanied by images of the dead fighters. The number of total YPG killed is presumably a little higher, for a while the YPG regularly announces its ‘martyrs,’ the process is frequently delayed. Rebel groups claim to have apprehended approximately ten YPG insurgents, however the YPG has verified one such instance within their press releases.

Between these three groups, only Ghadab al-Zaytoun has acknowledged attacks that have killed civilian bystanders. The first such incident was a car bomb set off in or adjacent to Souq al-Hal (Cardamom market) in eastern Afrin city on December 16. GaZ claimed it was targeting a passing patrol of fighters from the rebel group al-Jabha al-Shamiya, whose headquarters is reportedly within the vicinity of the market.

The statement said that “at least 25 mercenaries and settlers” were killed in the attack. By settlers, Ghadab al-Zaytoun is referring to the recently arrived displaced peoples from parts of southern Syria. They were able to flee north due to negotiations between the regime and the opposition. Turkey has chosen to settle most within Afrin, in what some have called intentional demographic change intended to dilute the region’s Kurdish character.

According to local reports, nine were killed and 13 wounded. It is unclear what portion of the casualties were civilians or combatants but video shot immediately after the bombing show it had a devastating effect on part of the marketplace.

With February drawing to a close, anti-TFSA insurgent groups have claimed 21 attacks during the month, a decline from December and January but consistent with the overall 23 attacks per month average. Less than half of these have been documented or corroborated. Nonetheless, a February 12 IED targeting a “Military Police” checkpoint outside the town of al-Ra’i and a February 21 car bomb in Afrin city, both claimed by Ghadab al-Zaytoun, demonstrate the continued reach the insurgency possesses.

While patterns have shifted — the YPG-branded campaign has ceased since December, Ghadab al-Zaytoun has ditched previous tactics in favour of car and motorcycle bombs, and ATGMs have seemingly replaced executions as an attention-grabbing technique — insurgent attacks show no sign of stopping. When taking in to account the enduring animosity between the PYD and Turkey, the continuing reports of human rights abuses and general lack of security in Afrin, the low casualty count suffered by insurgents, and no national peace process in sight, there is little reason to foresee this changing.

The data collected for this article, covering from March 2018 to January 2019, can be viewed here.

Edit: It has been brought to my attention by Twitter user @ddsgf9876 that there are at least 2 instances of YPG media using old footage of rebel attacks (a 12/15/18 ATGM launch in Sharran and a 12/8/19 IED in Bulbul), claiming them as their own. Further investigation into the authenticity of the early to mid December YPG videos is underway. The spreadsheet above has been updated with falsified attacks highlighted in red.