Weekend notes

On Maskanah: 19th century Ottoman efforts to settle it, its role in the Armenian genocide, and the fate of its sugar factory

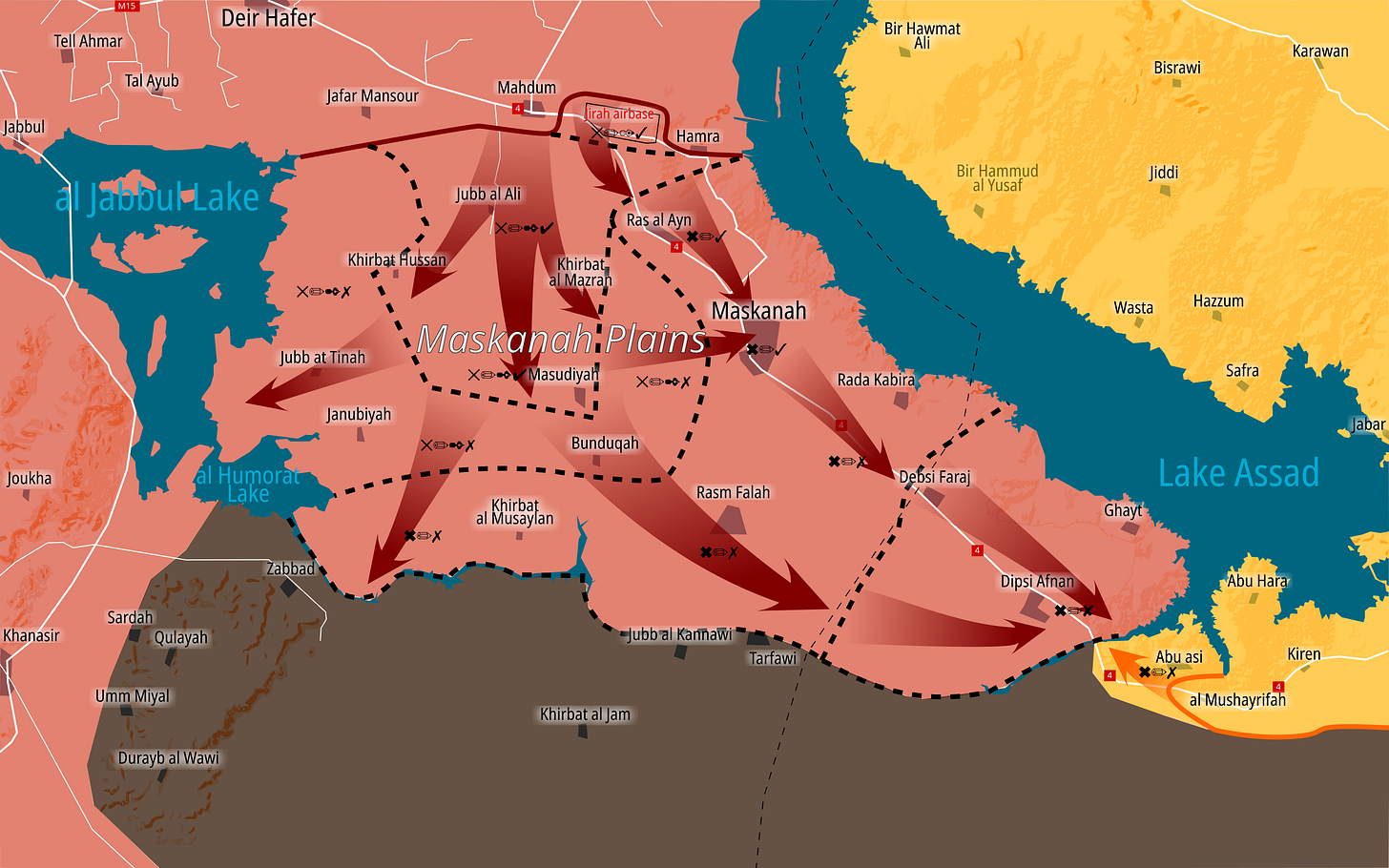

Maskanah is a town in eastern Aleppo, located on the right bank of the Euphrates near the al-Raqqah provincial border. It was captured from the Islamic State by the former regime in June of 2017, remaining under its control until the evaporation of the Syrian army in December 2024. Within the context of that vacuum the SDF entered, deploying forces in the direction of Aleppo city, up from nearby al-Tabqah to Maskanah and Deir Hafir. This salient solidified into the current front lines with the concurrent advance of the SNA into southeastern Aleppo.

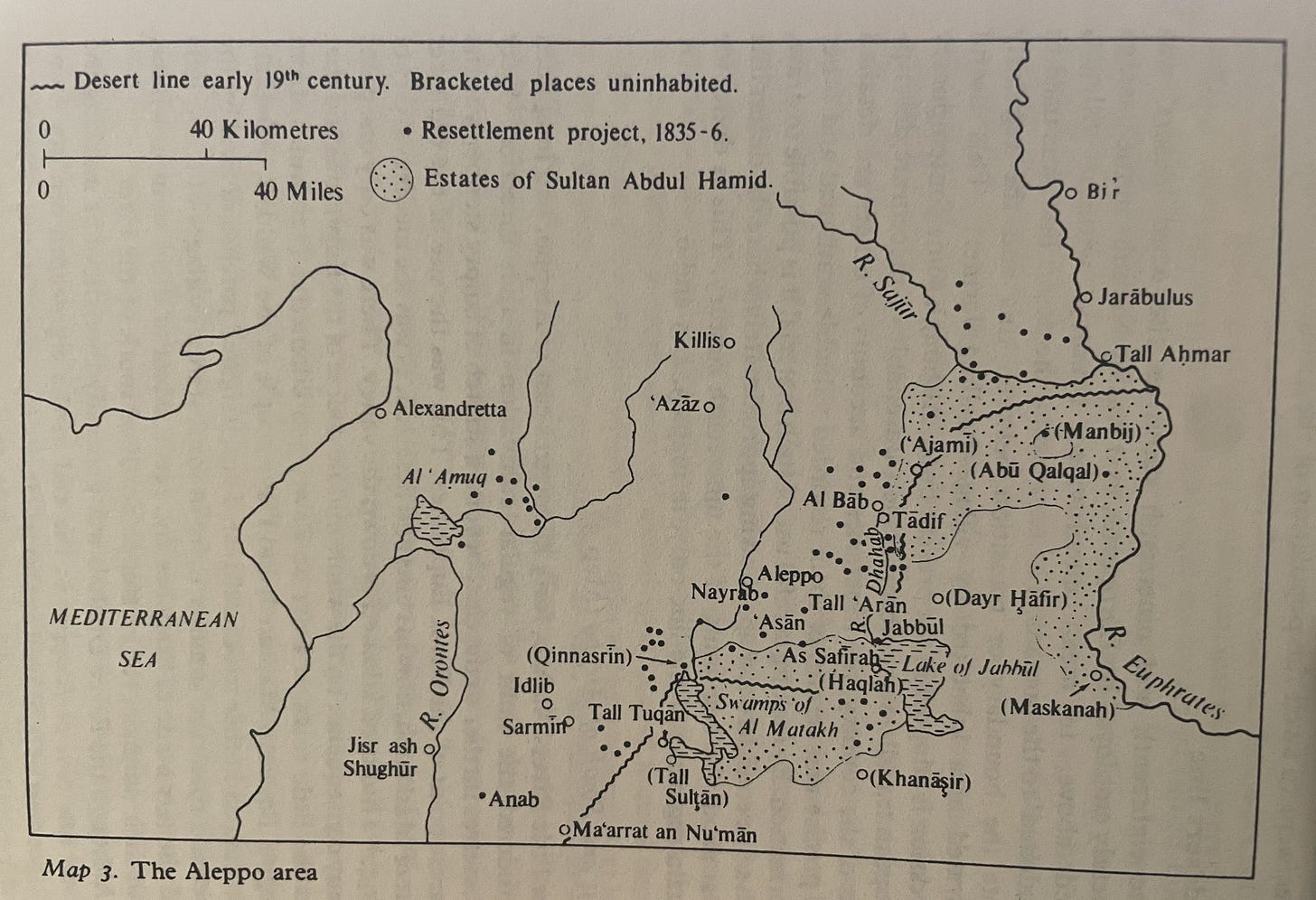

Like many other rural areas in the Levant, the population of eastern Aleppo ebbed and flowed over the course of the Ottoman’s four hundred year reign. According to accounts from the early 19th century, Maskanah and the surrounding countryside were largely empty, populated only seasonally by nomadic tribes coming north and west from the Badiyah and Jazirah. The excerpts below, from Norman N. Lewis’s Nomads and Settlers in Syria and Jordan, 1800-1980, cover this period and the ensuing attempts by the Ottoman state to subjugate the nomadic tribes and extend itself down the Euphrates,

The little River Dhahab, forty kilometres east of Aleppo, had long been considered the limit of regular cultivation in that direction. Fifty kilometres further to the east, beyond a stretch of empty steppe, was the nearest point of the River Euphrates. This was the site of the old river port of Maskanah, now in ruins and deserted, as was the mediaeval city of Raqqah a hundred kilometres down the valley. There was only one place of any consequence on the whole middle course of the Euphrates and that was the little town of Dayr az Zawr, 350 kilometres (220 miles) from Aleppo. Between Maskanah and Dayr people of the Wuldah, ‘Afadilah, Sabkhah and other tribes cultivated and irrigated villages of land by the river and spent the summer there in insubstantial villages of tents, huts and shelters made of branches and reeds. Most of them went in winter, with their animals, to the steppe north or south of the river.

Although the River Dhahab was generally thought of as marking the desert line* east of Aleppo, at the end of the eighteenth century many villages west of it, as well as almost all of those east of it, were deserted or under-populated. Tadif, near which the river rose, which had been described in 1737 as a ‘most pleasant village’, was ‘much declined’ by 1772. Jabbul, where the river entered the salt lake of the same name, and where salt was collected to be sent to Aleppo, was almost in ruins by 1751. Haqlah, on the western shore of the lake, was ‘among the last inhabited villages’ in that direction in 1772, and deserted at the end of the century. Even Nayrab, a big place almost at the eastern gates of Aleppo, was in a poor way in 1772 and described as ‘dévasté’ in 1782. (15)

*“the expression ‘the desert line’ was used to denote the boundary or transition between [uncultivated country] and the regularly cultivated area inhabited by village-dwelling farmers.” (15)

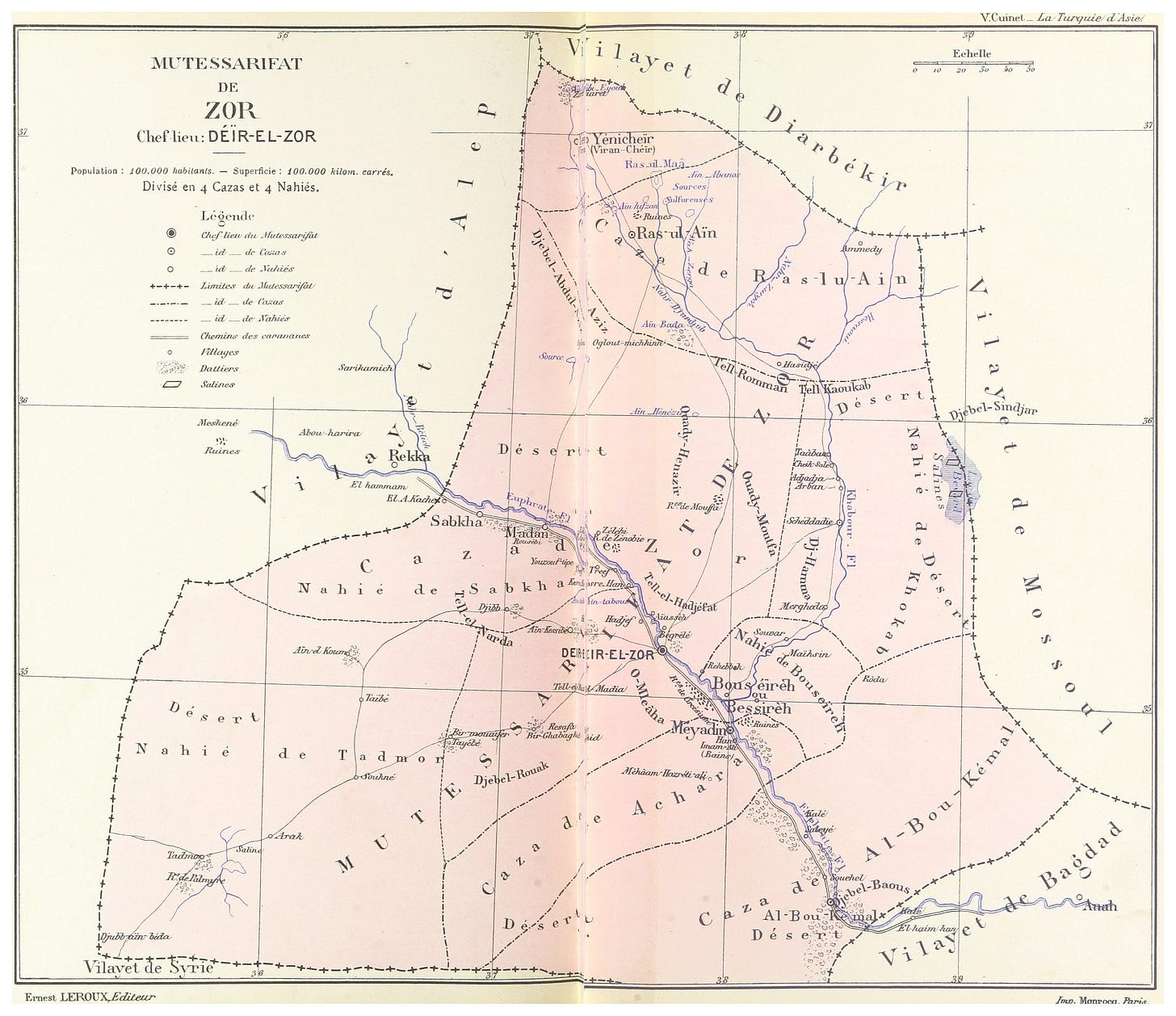

There was, however, consistency in government policy and, in particular, the goal of extending control to the Euphrates valley was not forgotten. The first significant step towards this end was taken in 1854 when a new administrative district, the Mutasarriflik of the Zawr, was created. The Zawr was the name used locally for the whole middle part of the valley from Maskanah to Dayr az Zawr and beyond, but the officer put in charge of the new Mutasarriflik was only able to operate near Maskanah. In this area, the nearest part of the valley to Aleppo, he raised a force of irregulars, collected taxes from the riverine tribesmen (who of course objected to paying taxes as well as khuwah to the Fid‘an) and built some small military outposts.

It was obvious to all that the riverine tribes were not the only target of all this activity and in July 1857 a major attack was made on the Fid‘an… After an engagement which lasted two hours the official casualty figures were 300 beduin killed or wounded, eleven soldiers killed and twenty wounded. Needless to say, the beduin version of the affair was very different.

The clash too place twenty kilometres or more below Maskanah, on the right bank of the river; this was the first time that the army had struck at the Fid‘an so far to the east, in the Zawr itself, which the beduin had regarded ‘as their granary and strong-hold’. The inclusion of riflemen amongst the troops was also noteworthy… one of the first indications of dominance which the forces of the State would eventually establish.

The army followed up this success by establishing a camp ‘at the furthest point of cultivation’. This was probably in the vicinity of Maskanah, the centre of the new Mutassarriflik and the obvious base for operations further down the valley. It was also one of the main summer camping areas of the Fi‘dan who made frequent use of the nearby fords across the Euphrates. The Fi‘dan now had to suffer troops in their midst here as well as in their camping grounds further west. (27-28)

[In 1906 Mark Sykes] again visited Aleppo and then west east to the Euphrates, writing on his return…

“On the way from Haleb to Meskene, as far as the eye can see, there stretches a glorious tract of corn-bearing land, spotted with brown mud villages, contained a mixed race of people who reply equally readily in Turkish, Kurdish or Arabic to the questions put by the passing traveller. Many of these villages are the property of wealthy citizens of Haleb whose influence is sufficient to obtain protection for their tenants from the Government. The cultivation is not elaborate, but the ground is fairly tilled, and the continual influx of industrious peoples is steadily regenerating the land. The prospect of a multitude of villages growing up in a gouncty which once before supported a great and wealthy population, is more than pleasing to the eyes. At present the reclamation only extends within an hour of Meskene; but as the most easterly villages were only built last year, there is every hope that within a short time the river banks themselves will be populated.” (55)

Later on Maskanah played a role in the Armenian genocide, serving as the site of a concentration and deportation camp to which the Ottomans sent mass of Armenians - either to die there or to be sent further down the river into Deir ez-Zour. Excerpt from Syrian Armenians and the Turkish Factor: Kessab, Aleppo and Deir ez-Zor in the Syrian War, Marcello Mollica & Arsen Hakobyan.

For the deportees, the “Euphrates line” became synonymous with death; along the line, there was a succession of camps, such as Meskene, Dibsi (Faraj), Abu Hajaar, Hamam, Raqqa and Deir ez-Zor. The camp in Meskene was one of the deadliest. This was both a concentration and a transit camp to Deir ez-Zor. According to the head of the camp, Huseyin Bey, 80,000 Armenians died there in 1916, but the number could be much higher. The Dipsi camp was where people from Meskene were brought to die; it operated only for six months, from November 1915 to April 1916; yet 30,000 people died there. The last destination was Deir ez-Zor; there and in the surrounding area are located many spaces of mass killings like, for instance, Marât. Big convoys were broken down into groups of 2,000–5,000 people who were forced to a two-day march in the desert to reach As-Suwar, in the Khabur Valley. There, people were grouped together on the basis of their place of origin. Men were separated from women and children and mostly killed. Women and children were put on the road to Sheddadiye, where they were usually killed behind a hill overlooking a nearby Arab village. (82)

From antiquity up through the middle ages Maskanah and the nearby Bronze Age city of Emar represented a key regional transit node. Today the most notable landmark is a 13th century brick minaret located just outside Maskanah near the banks of the Euphrates, just above the Emar site.

The 13th century brick minaret at the site was originally constructed in the now submerged village of Siffin (صفين). When the valley was threatened with flooding in the early 1970s, a rescue campaign was undertaken to move the minaret to its current location. It was near the village of Siffin (صفين) where the historic battle between Ali and Muawiya took place in 756, deciding the fate of the Umayyad dynasty. The most impressive monument at the site, the octagonal minaret features several Arabic inscriptions and geometric patterns and demonstrates eastern architectural influences during the Ayyubid period. An interior staircase leads to the top of the minaret, with fantastic views of the lake and surrounding countryside.

Economically the most significant site in the area is the state-owned sugar factory, looted and greatly damaged by the end of the former regime’s capture of the region from the Islamic State. The Qaterji group was hired in 2021 to rehabilitate the factory - a process that took two years, though production wasn’t actually schedule to begin until September 2024. The video below is from November 2023, detailing the reconstruction process and bureaucratic hold ups.

04/30/21 vs 10/18/24:

Turkey bombed the factory several times in early January 2025 after it had fallen into the hands of the SDF, severely damaging it (significant damage dealt to the central building and the building just east of the green).