Weekend notes

Urban notables of Damascus, Turkey's education policy in Syria, and July on the Euphrates

Urban Notables and Arab Nationalism: The Politics of Damascus 1860–1920, Philip S. Khoury

At just 100 pages Khoury’s Urban Notables is a short and succinct study examining the “landowning-bureaucratic class” of late Ottoman Damascus and its role in developing Arab nationalism as a political movement. While its focus is on the emergence of Arabism, the book’s analysis of social conditions and class composition make it valuable in understanding the creation of the political elite that largely dominated Syrian politics up until the mid twentieth century. As is always the case when discussing modern history across the Levant, central to this story are the Ottoman Empire’s Tanzimat reforms (1839-1976), which attempted to modernize and centralize imperial administration in the face of increasing European pressure. The Land Code of 1858 was particularly vital, which was intended to increase state revenue by getting rid of tax farming but instead saw tax farmers and other notables accumulate large tracts of private property due to peasant hesitancy to register property with the state (Zionist ability to purchase land from absentee owners being a direct effect of this reform).

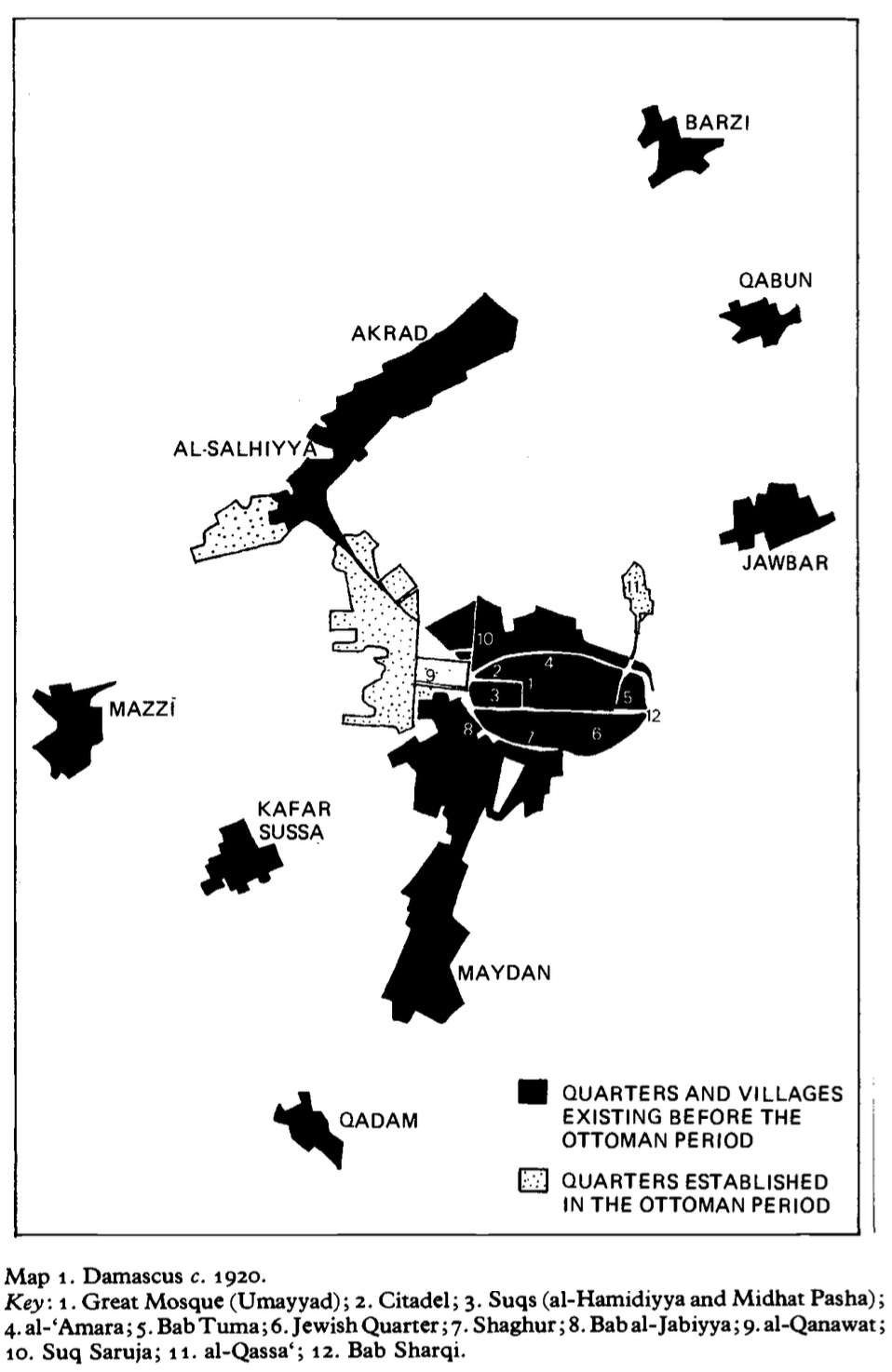

In response to the 1860 massacres in Damascus, in which mobs stoked to some degree by political elite slaughtered thousands of Christians in the Bab Touma neighborhood, Istanbul seized the opportunity to disempower the local notables. Prior to 1860 this consisted of the ‘uluma’ - the clerical establishment, the aghawat - janissary chiefs (many actually being Kurdish tribal leaders deployed from modern day Turkey), and an assortment of tax farmers and merchants, who either held seats in the local majlis or wielded significant economic power (ie. Aghawat dominance of the grain and livestock trade). What emerged after was what Khoury terms the “landowning-bureaucratic class,” comprising families of the pre-1860 and newcomers shaped by the new structural reality…

During the next fifty years the Ottoman government managed to remold the Damascus power structure in three important ways. First, with a stronger provincial administration controlled more efficiently by Istanbul, the exercise of local political power became a function of position in the bureaucracy. Consequently, maintaining and expanding wealth and influence depended on securing high administrative office. Instead of being a tool to wield against the state, possession of independent power became a means of access to it. Exclusion from the bureaucracy generally meant loss of independent influence and therefore loss of access to those with authority. Secondly, since the Ottoman government was the sole distributor of offices, it became necessary to identify with the interests of Istanbul to acquire a post. Thirdly, the creation of powerful secular institutions meant that greater influence was derived from office in these institutions rather than from the traditional religious institutions. Thus, after 1860, the political leadership of Damascus underwent a significant metamorphosis owing to the diversification of its power base and the change in its political orientation. (83-94)

The measure of political power in Damascus was a combination of two interconnected sets of relationships. The first concerned the family unit's ability to attract a clientele by constructing a series of vertical linkages through society binding individuals and groups to the family. The second pertained to the family unit's ability to make key alliances with other family units, in the process binding clientele networks together. After 1860, the success a Damascus family had in combining both sets of relationships to achieve significant political power was determined by its ability to secure offices. Offices could in turn be manipulated to build and enlarge a family's material resource base. Offices and wealth together created a pool of benefits or services with which a family could attract clients and make alliances with equals. (94)

According to Khoury the landowning-bureaucratic class was largely wedded to the Ottoman empire until quite late, with the few pre-war examples of Arabism within its ranks advocating pushing for decentralization rather than independence.

While most of the Syrian Arabs trained in Istanbul for Ottoman service were concerned with what needed to be done to keep the Empire afloat, and some even were critical of the ruling establishment's policies in Istanbul, very few found reason to express their discontent in terms of their 'Arabness.' Indeed, it was only after the Young Turk' revolution' of 1908 that some of these urban notables and officials of the state began to feel increasingly estranged from the' inner circle' of the Ottoman elite, which had always been mainly Turkish. As some notables were excluded from the Ottoman system of rule and denied access to the central authority, they found a need to restate the ideas they had picked up in Istanbul in terms better suited to their changed circumstances. Their search for these new terms did not take long, since already available to them were two versions of Arabism, one articulated by Syrian Christians and the other by Syrian Muslim reformers. (97)

The important point to underscore, however, is that before World War I the mainstream of the Arab movement sought neither the separation of the Arabic-speaking provinces from the Ottoman Empire nor the creation of a distinct Arab nation with defined cultural and territorial boundaries. Rather the movement desired more modest changes, in particular greater measures of administrative decentralization and political autonomy for the provinces. Its goals, elaborated within the ideological context of Arabism, reflected the interests of a certain fraction of the urban absentee landowning class that had failed to achieve political power commensurate with its expectations. In this period the Arab movement did not achieve its goals. (97)

This Ottomanist tendency would only end with the severing of the empire from Arab lands by the Entente at the end of World War I and the creation of the short-lived Faisal monarchy.

Omar Kadkoy on “Turkey's reach into Syrian education”

Turkey’s post-conflict engagement with Syria signals a clear intent: to entrench its influence through the education system. By investing in academic integration, promoting Turkish language instruction, and cultivating a class of Turkish-educated Syrian elites, Ankara is embedding itself in the intellectual and institutional foundations of Syria’s future. This approach advances Turkey’s geopolitical interests and positions it as a civilizational partner, shaping Syria’s intellectual reconstruction from within. Syria’s best and brightest might still aim for institutions in the West, but its entrepreneurial and culturally rooted students will probably want to learn Turkish.

Photos taken by Charles Cuau during a July trip across the Euphrates front lines

Accompanying French language article “‘People are afraid of war’: on the banks of the Euphrates, the quiet conflict between Arabs and Syrian Kurds,” by Pauline Vacher

A tank destroyed in December 2024 during the SNA’s Manbij offensive, on the M4 highway just west of the Qaraqozak bridge

Views eastward from Qal‘at Najm featuring two SNA fighters

al-Tabqah dam, aka Furat/Euphrates dam

Kids visiting Qal‘at Ja‘bat on the SDF-controlled left bank

Fishing at dusk with a view of al-Raqqah and the DAANES Executive Council buildings