On SETA's Deleted 'The Syrian National Army' Report

Bu metin Dünyadan Çeviri tarafından Türkçeye çevrilmiştir.

On November 18, Turkish think tank SETA published a report written by research assistant Ömer Özkizilcik titled “The Syrian National Army.” This work was reportedly based on field research and a survey of Syrian National Army (SNA) fighters conducted by the author. After Twitter users highlighted that some of the report’s data implied the use of child soldiers by this Turkish-backed Syrian militant organization, SETA and Özkizilcik quickly deleted the report and tweets highlighting its findings. Due to individuals quickly archiving a PDF copy of the paper on the Internet Archive Wayback Machine, it is still available to the public. The report is quite interesting in several regards as it is the first empirical survey of the SNA and its membership. Additionally, the author’s overwhelming pro-Turkish biases both inform the results in noteworthy ways and highlight how such discourses regarding the SNA diverge from those of somewhat sympathetic western observers.

First, several things must be said about SETA, or the ‘Foundation for Political, Economic and Social Research,’ founded in 2006. The think tank has long enjoyed close ties with Erdogan and the AK Party. It’s founding director, Ibrahim Kalin, is currently Erdogan’s presidential spokesperson, and has worked in advisory roles to the president for years. The German government has stated in response to parliamentary inquiries that the organization is largely funded by the family of Berat Albayrak, Erdogan’s son-in-law and Turkey’s recently resigned finance minister. SETA is most infamous for a 200 page 2019 report it published, extensively naming and documenting Turkish journalists working in foreign press agency allegedly holding an “anti-government” bias. Given that Turkey ranks among the worst in the world in terms of press freedoms, an AKP-aligned think tank publishing such a list justifiably raised significant concerns.

In his introduction, Özkizilcik clearly states that his motivation in conducting and presenting this research is to draw clear continuities between the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army and the ‘Free Syrian Army,’ an immense patchwork of anti-Assad militias founded from 2012 on, some of which received significant American support until 2017. These efforts of his are written against those that consider the SNA to simply be Turkish proxies, or those that “portray the Syrian National Army as a collection of mercenaries or fighters who are motivated solely by money.”(9) This, in turn, would serve to both justify ongoing Turkish policy with regards to the SNA and to lobby western support for this militant structure, or at the very least a reconsideration of current American and European support for the Kurdish-led SDF.

The survey the report rests on was conducted via Google Docs in December of 2019, augmented in some unclear capacity with two trips undertaken by the author to territory controlled by the SNA and Turkey. Özkizilcik claims that the data analyzed includes the responses of 1,551 fighters from each of the three legions making up the SNA. This sort of empirical research into the Syrian opposition is unprecedented, therefore inherently holds some value, though must be scrutinized with the author’s biases and position in mind. The fact that Özkizilcik was able to conduct field research in Turkish-controlled northern Syria - in the areas of “Tal Abyad, Suluq, Tal Khalaf, Rasulayn, Azaz, Al-Rai, Afrin, Jinderes, and Shaikh Hadid”(13) – demonstrates extraordinary access. Turkey strictly controls who is allowed to enter these areas, with international journalists and monitoring organizations almost completely barred. That Özkizilcik was able to tour such locales, including “Tal Abyad, Suluq, Tal Khalaf, [and] Rasulayn” between “November 22, 2019 – December 3,” as Turkey’s Operation Peace Spring was ongoing, exhibits the close relationship SETA enjoys with the Turkish state.

The survey itself consisted of nineteen questions related to the fighters’ demographic profiles, motivations, financial situations, and opinions regarding the current state of the conflict and the international actors involved. Of the 1,551 survey participants 40.87% belong the 2nd Legion factions, 30.16% to third, and 28.98% to the first. It’s unclear how representative of the actual legion sizes this is, but the author states that this confirms that the 2nd Legion is the largest, a fact he somehow gleamed during field research. He states that the total size of these legions is between thirty and forty thousand; as is this case with all estimates of manpower in Syria there is no way to confirm nor deny such figures. The report includes two helpful graphics relating to the structure of the SNA, its leadership and affiliated brigades. However, there are two ways in which these charts can possibly mislead readers.

When brigades and their respective legions are laid out like this it can apply equivalency, logo to logo. However, factions vary greatly in size and do not necessarily correlate with traditional military structure. Some may number no higher than the low hundreds or even in the couple dozens, while some of the larger militias may field thousands of fighters. Additionally one must be wary when examining the formal structure of the SNA and its placement beneath the Syrian Interim Government’s (SIG) Ministry of Defense and General Staff. In reality, most of these factions feature personalized leadership, in which individual personalities and their associates jealously defend their power and autonomy. SNA factions have proven time and time again to be prone to infighting and criminality, only falling in line with SIG hierarchy when it suites their interests.

It was the first two questions of the survey, “How old are you?” and “How many years have you been fighting?,” that drew immediate attention to the report. 7.85% of the survey participants were found to be within the 18-20 range, while 6.78% said that they’d only been fighting for under four years (since the SNA was first announced).

This discrepancy led many to say that the report had highlighted SNA usage of child soldiers, an allegation that has been cast against the Turkish-backed opposition structure for years (see this report covering SNA child soldiers being sent by Turkey to Libya). Without access to raw survey data of all 1,551 participants these allegations cannot be proven, however the fact that the report was quickly deleted by SETA certainly raises eyebrows. Regardless, this data does cast doubt on the claims that the majority of SNA fighters were recently recruited by Turkey or Turkish-backed commanders, and did not partake in earlier fighting against the Syrian regime. This line of argumentation is typically put forth by those seeking to separate earlier Syrian opposition forces that received western support from the current Turkish SNA project, in order to defend the reputation of the former. It is interest to see the divergence in discourse between those making this aforementioned point, and others, such as Özkizilcik, who have ardently supported both the earlier armed opposition and this ongoing Turkish SNA project. Personally I am of the opinion that the significant continuity portrayed in this survey is quite real, but that one must also account for the significant contextual changes that have occurred since a handful of pivotal events in 2015 and 2016 (collapse of the PKK peace process, Russian intervention, US disengagement, Turkish coup attempt and others). Many of the fighters and a number of the factions have remained a constant, but Turkey has channeled their attention away from Assad in order to carry out its anti-SDF, anti-Kurdish policy objectives.

Another interesting aspect of the survey is the ethnic breakdown of the SNA legions. The report finds that a large majority of SNA membership is Arab (87.73%), while only 10.53 percent are ethnic Turkmen. When broken down into affiliation, the heavy representation (20.32%) of Turkmen within the 2nd Legion becomes clear. This both points to the numerical size of groups like Furqat al-Sultan Murad, Furqat al-Hamza, and Furqat al-Mu‘tasim. Conversely this suggests that the Turkmen branded groups in the 1st Legion, such as Liwa’ Samarqand, Liwa’ Muntassir Billah, Furqat al-Sultan Suleiman Shah and others, are either quite small, or include significant numbers of Arab fighters.

This points to my assumption that many reports on the SNA, its behavior, and the demographic changes in northern Syria (such as the ethnic cleansing of Afrin) have overblown the Turkmen angle numerically. However, this is not to downplay the importance of Turkmen within the dynamics of northern Syria. Given ethnic affinities and the years of close relations between Turkmen factions and Turkish intelligence, Turkmen factions appear to possess a privileged position in terms of Turkey’s ongoing Syria policy. It was three explicitly Turkmen or Turkmen-led factions that spearheaded the SNA deployment to Azerbaijan (Furqat al-Sultan Murad, Furqat al-Hamza, and Furqat al-Sultan Suleiman Shah), a dynamic I believe points to the trust Turkey places in these factions and their commanders. While the math is a little unclear it seems that 22 of the 1,548 fighters that responded to the ethnicity question identified themselves as ethnically Kurdish. Of these, all answered positively to a latter question regarding their opinion on Turkey’s role in Syria. Neither the small size of Kurdish SNA fighters, nor their pro-Turkish politics is particularly surprising, instead correlates with the current scope of Kurdish participation in other Turkey-backed opposition institutions.

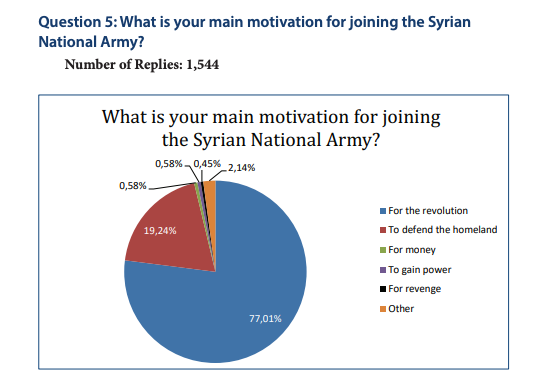

The survey also asked fighters what their primary and secondary motivations were regarding their motivations to joining the SNA. The results show that a majority responded that they joined “for the revolution,” with “to defend the homeland” coming in second.

The report clearly framed this question in response to allegations of SNA fighters simply being mercenaries, joining “for money.” The response received appears to clearly refuted this. However, it must be assumed that a significant degree of confirmation bias exists within these results, and that few would openly admit to joining for material reasons. These questions regarding motivation must also be viewed within the contexts of professed monthly family income, with 64.63% answering the survey question with “Less than 500 Turkish Lira,”($66) as well as the fact that thousands of SNA fighters have taken part in two recent Turkish campaigns abroad, completely unrelated to the Syrian conflict, and were offered significant pay raises to do so.

The questions relating to opinions regarding the state of the conflict and the international actors involved do not offer many surprises. SNA fighters support Turkey and dislike the role of the U.S., Russia, and Iran (in particular). The majority think that the Astana Process is not useful, though a quarter answered that it is. The vast majority said that they “believe in the fall of the Assad Regime,” though it is unclear whether this refers to prognostication or desires. Almost exactly half of those asked say that a political solution is possible. Most interesting of all these answers is the fact that 47.95% say that the work of the SIG is not useful, showing significant divergences between the Turkish-backed armed opposition and the Turkish-backed civilian opposition, differences that are visible in terms of how the former sometimes treats the demands of the latter.

Unique in that’s the first empirical study of its kind, this survey does give us some insight into the Syrian National Army, a militant structure who’s innerworkings are often veiled by its real life lack of structure and the general lack of access to Turkish northern Syria awarded to the international community. Arguably, the key finding is that a significant majority of SNA fighters have participated in the armed opposition for years, predating this Turkish initiative that began in late 2017. While those that are supportive of the SNA, such as Özkizilcik, may overstate the continuity between the elements of the pre-2017 opposition receiving western support and this iteration, it cannot be dismissed.

Personally I believe that in order to properly understand such continuity, a more granular inquiry into how western support functioned, who received it and when, and the role such actors play now within the SNA is required. A simple chart with logos does not suffice.

The report, including further breakdowns of data by ethnicity and legion can be accessed here