Afrin: Incidents Of Desecration And Destruction Of Cultural Sites

originally published on bellingcat.com

Soon after the inception of Turkey’s Operation Olive Branch in January of 2018, reports began trickling out of Syria’s Afrin district detailing the desecration or destruction of numerous cultural sites in the region. Just two days into the operation, airstrikes inflicted significant damage on Ain Dara, a “Neo-Hittite temple…built by the Arameans in the first millennium BC.”

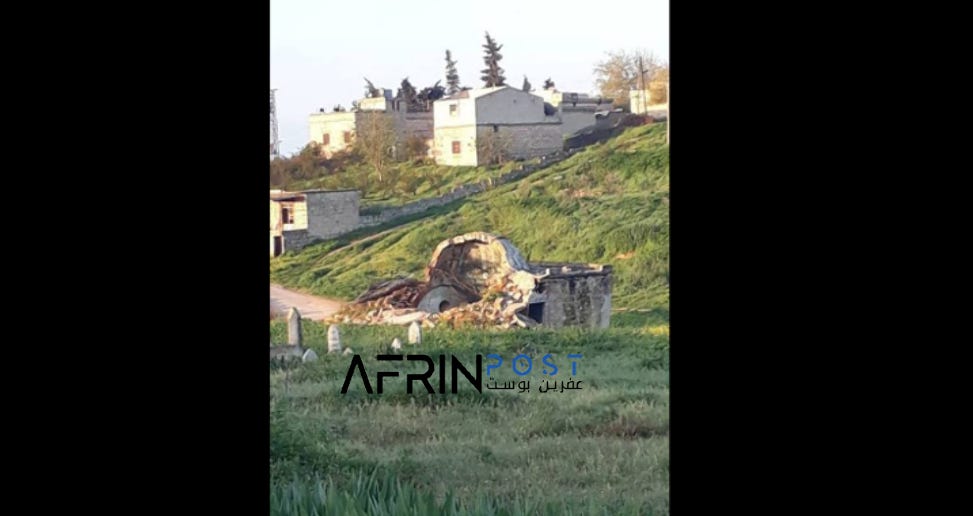

The ASOR (American Schools of Oriental Research) Cultural Heritage Initiatives published a report on the incident, detailing the damage and concluding that “attributions of the damage to a Turkish airstrike(s) are credible.” The March 18, 2018 capture of Afrin city by Turkish-backed forces culminated in the symbolic destruction of the Kawa statue which depicted a hero from Kurdish (and Persianic) folklore, who, to millions, symbolizes freedom from tyranny.

For the next four months, ASOR continued to monitor and chronicle similar allegations from Afrin with their Safeguarding the Heritage of the Near East Initiative reports. While publication of these dispatches ceased for unknown reasons in May 2018, this article seeks to further investigate and add to the data they collected regarding incidents of desecration and of destruction visited upon cemeteries, religious shrines, and other cultural sites within Afrin during and after Turkey’s Operation Olive Branch.

While the damage exacted on such sites investigated here makes up only a portion of reported abuses inflicted on Afrin and its inhabitants by Turkey and its local partner forces, such incidents can be verified and documented remotely, using OSINT techniques.

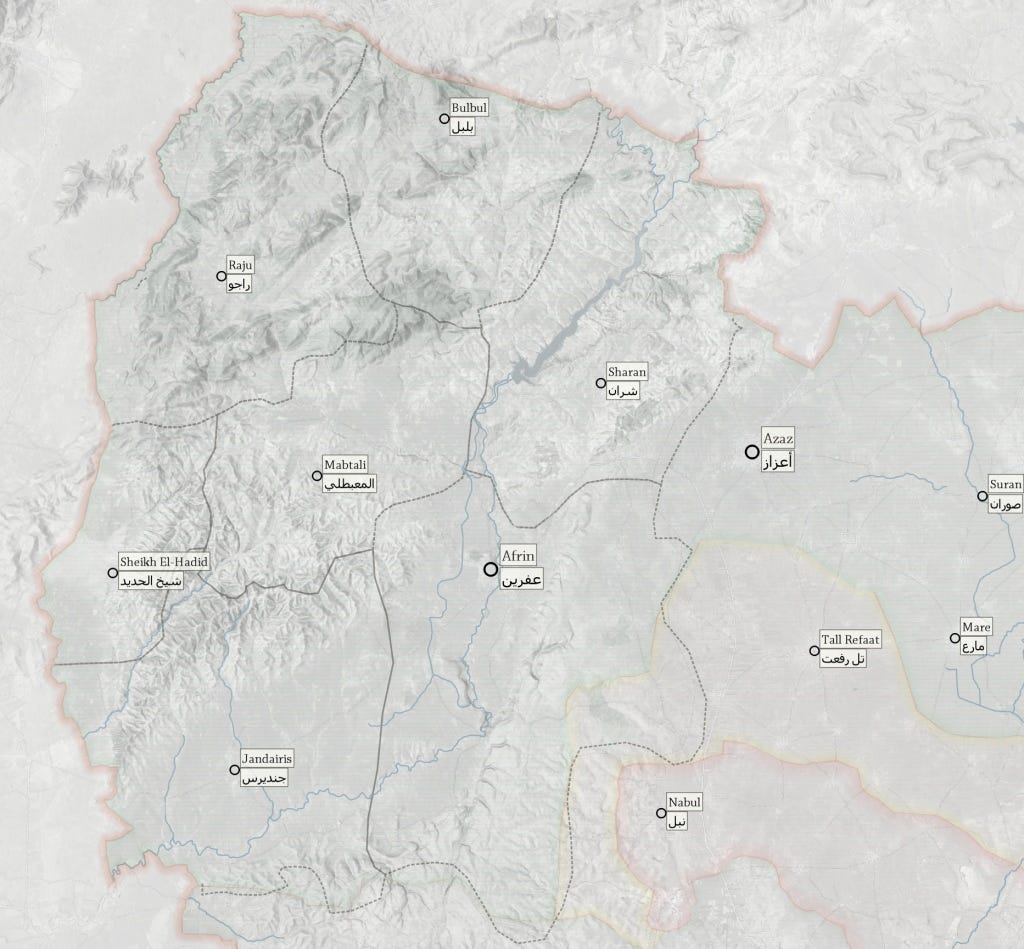

Located in the northwestern corner of Aleppo governorate and bordered by Turkey to the north and west, Afrin (also known as Kurd Dagh) is known for its olive industry and picturesque rolling landscapes. The region’s pre-war population of approximately 200,000 was almost entirely of Kurdish ethnicity, with a small Arab minority predominantly living in the south. Throughout the Syrian Civil War, Afrin absorbed numerous Kurdish and Arab Internally Displaced People (IDPs) from other parts of the country’s north. However, as many such IDPs, as well as Afrin’s original inhabitants, have left Syria over the last eight years, it’s unclear what the demographic makeup was prior to the start of Turkey’s Operation Olive Branch in January 2018.

By the latter half of the twentieth century, Afrin had developed a rather secular reputation. According to historian Harriet Allsopp, author of The Kurds of Syria: Political Parties and Identity in the Middle East, the region had the fewest mosques nationwide and its inhabitants were typically not strict adherents to religious conventions. However, Afrin was home to vibrant Sufi networks, as well as small Yezidi, Alevi, and Christian populations. The region’s Sufis, Yezidis, and Alevis maintained shrines throughout the countryside, often the tombs of sheikhs and holy figures, which acted as the frequent locus of pilgrimages and communal celebrations.

Yezidi presence in the region dates back to at least the 13th century. Estimates typically place the pre-war population somewhere between 5,000 and 15,000, largely residing within three clusters of villages in Afrin’s south and east. It’s unclear how many Yezidis still resided in Afrin immediately prior to the Turkish invasion. Few remain in the area today. The majority of the community fled east to other PYD-controlled enclaves, such as the Shahba region of Aleppo, today reportedly home to around 6,000 Afrini Yezidis.

There are approximately fifteen Yezidi shrines in Afrin and the Jebel Sim‘an region to the south. These shrines commonly are found in the vicinity of Yezidi cemeteries, and feature nearby trees which worshippers tie ribbons on, symbolizing their wishes. Due perhaps to close communal proximity, as well as to the widely espoused view that a portion of the region’s Muslims are the products of Islamization campaigns conducted in Yezidi towns, syncretic usage of such shrines appears to have been common, as was the case with the Qara Jorna shrine, which we will talk about in more detail below.

While their religion and identity was historically repressed by the Ba‘athists, the withdrawal of the regime from the area in 2012 saw a flourishing of Yezidi religious and political activity in Afrin. This is apparent the formation of organizations such as the Yezidi Association, which has worked to both education and organize the community.

Likely the only Kurdish-speaking Alevi community in Syria, the Alevis of Afrin arrived over the past several centuries, escaping bouts of persecution in Anatolia. The most recent influx in the wake of massacres perpetrated by the Turkish Republic in the wake of the 1938 Dersim uprising. Afrin’s Alevis live within the centrally located Ma’abatli (also known as Mabata) subdistrict. The community’s size is estimated to be somewhere between a “few thousand” to 15,000, however, as the 2004 census listed Ma’abatli’s religiously-mixed population at 12,359, the former is more likely.

Interviews with Afrini Alevis from the last several years suggest the community had suffered a “loss of the faith and culture of the Alevi people [while living under] the Arab regimes.” Similar to the experiences of Afrin’s Yezidis, Alevis were able to both practice their faith freely and organize politically under the PYD’s “Self-Administration” project, this being most evident in the 2017 opening of an Alevi cultural center in the Ma’abatli area.

Afrin’s contemporary Christian population is quite recent and made up of Kurdish converts to the Evangelical Protestant Church of the Good Shepherd. Since Operation Olive Branch, it appears that the entirety of Afrin’s Christian population fled east to other areas under the control of the PYD. In May of the same year, it was reported by local activists that the Afrin church had been plundered by two opposition factions. In a September 2018 article for news outlet Kurdistan24, journalist Wladimir van Wilgenburg reported on an evangelical Church opened in Kobane by exiled Afrini Christians.

Since March 2018, Afrin’s demographic makeup has undergone immense changes. Large portions of the region’s heterodox populations fled following the start of Operation Olive Branch, followed soon after by Turkey’s resettling of Sunni Arab IDP’s fleeing the Assad regime into abandoned homes and newly constructed camps. It is within this climate that the following incidents of desecration and destruction to cultural sites has occurred.

As previously detailed in this November 2018 Bellingcat report, the hilltop Ali Dada shrine and portions of the adjacent cemetery, located just east of the town of Anqele, were leveled during the construction of a military position. This destruction occurred at some point between February 26t and March 5 of 2018, soon after the town had been captured. It’s unclear whether the parties responsible belonged to the Turkish Armed Force or to local allied forces active in the area at the time, such as Liwa al-Vakkas or the Syrian National Army’s 1st Legion. The name “Dada,” or “Dede” is the title used by Alevi clerics, and is found in the names of many local shrine. However, due to the Ali Dada shrine’s location on the outskirts of a Muslim village, it’s likely that non-Alevis utilized the shrine as well.

On March 27, 2018, a Yezidi media outlet, Ezdina News, published a video that had originally been uploaded on a private Facebook page, showing the desecration of the Qara Jornah Shrine. The video shows several men allegedly affiliated with Olive Branch forces mocking the shrine and its adherents while burning strips of cloth tied to a tree outside, as well as before and after footage of the shrine’s interior, demonstrating that some intentional destruction had occurred. Two of the people in the video are in civilian clothes, while one is wearing military webbing, however there are no marks identifying which brigade he belongs to.

The shrine is located here, within the northeastern subdistrict of Sharran, and is frequented by both the local Yezidi and Muslim communities. According to a 2011 article on local Northern Aleppo website ESyria, which reported on locations and cultural sites in the area prior to the war, locals would come to the shrine each Wednesday in order to make a sacrifice and die a ribbon to one of the nearby by oak tree in the hopes of having their wishes fulfilled.

The sacrifice often took the form of a chicken, which would be cooked at the site and then either eaten or given to passers by or the needy. Such trees, typically oak trees thought to be hundreds of years old, are frequently found in the vicinity of religious shrines in Afrin and are revered and protected by local custom.

The shrine of Nabi Houri sits to the southwest of the ancient city of Cyrrhus at the site of a Roman mausoleum (located here) and “has been venerated since the 14th century as the burial place of one of the prophetic predecessors of Muhammad” — as documented by anthropologist Paulo Pinto.

According to Pinto, the shrine attracts pilgrims from Sufi lodges throughout northern Aleppo, coming yearly to celebrate the saint. A Facebook video posted on 3/18/18 claimed to show the disruption of the shrine site, at the bottom of the hexagon tower.

Pro-opposition news network Orient TV shot a segment at the same site the previous month, at one point showing the shrine room. In the Facebook video, the lectern located within the shrine room has been flipped over, but due to lack of imagery extensively showing the shrine before Operation Olive Branch, it’s unclear if other items are missing or have been distrubed. Attributing the allegation to a local source, ASOR reported that “FSA fighters allied with Operation Olive Branch ransacked the shrine looking for treasure.” A 2010 article on website ESyria highlights the history of the mosque located right next to the tower.

On April 11, 2018 a Facebook page named the Kurdish Legal Authority published a photo claiming to show destruction inflicted on the Madour shrine located in the Bulbul subdistrict. The shine is mentioned in an article by local website Tirej Afrin as being located on a hill to the west of the town Qirigole.

The second image in the Facebook post, quite possibly taken at an earlier time, shows this hill with a building on top, located here, that’s surrounded by foliage similar to that in the first picture. As of yet, we have not been able to confirm that this is the correct location, or corroborate the damage to the front wall through satellite imagery, however the Facebook photo appears to be original as it does not appear in reverse image searches.

On May 18, 2018, photos were circulated through social media and various news outlets showing the desecration of the Sheikh Zayd shrine. The images show that the contents of this shrine have been torn out and dumped outside, while the floor has been dug up. Several more images can be seen in the Hawar News article.

The shine, located here, sits within a cemetery in northern Afrin city neighborhood of Zaydiyyah. Pro-opposition news agency Aleppo24 reported on the incident accusing “gunmen from the Afrin operation” as the perpetrators in this desecration.

Ezdina News published a video showing the desecration of a second Yezidi shrine on May 21, 2018. It shows the tombstone found on a single grave within the small one room building having been taken down and smashed, while the grave itself has been opened.

This shrine is named for Sheikh Junayd, a Yezidi cleric who died in the 1930s, and is located just outside the town of Feqira (also known as Qarah Bash). The Ezdina News video also shows clips from the shrine’s dedication in 2011. Interestingly, as perhaps the most recent Yezidi shrine in the region, Sheikh Junayd features a fluted conical dome, such as those found in the Yezidi areas of Iraq.

The Sheikhmus shrine, found in a cemetery south of the town of Gewenda in the Rajo subdistrict (exact location here) was reported to have been ransacked on June 16, 2018.

Photos allegedly from the site surfaced several days later on Facebook, reportedly showing the main room of the shrine having ransacked and excavation having occurred at another part of the shrine.

Eight months later, in February 2019, photos and video surfaced showing many of the trees surrounding the shrine to have been seeming chopped down at random. More information on the Sheikhmus shrine can be found in this 2014 ESyria article.

On June 21, 2018, the Kurdish Legal Authority published a video to their Facebook page showing the desecration of another Yezidi shrine, this time the Sheikh Rakab shrine (location here) in Shadira village, south of Afrin city. A portion of the ceiling collapsed and the rest of the room and the grave it hosts are covered in debris.

According to the KLA, Turkish-backed forces had entered it in search of “gold and relics.” The shrine contains the body of “famous Yezidi community leader Sheikh Huseyn Brimo” (as per Sebastian Maisel’s book), who was buried there after his death in 2013.

A second Alevi shrine was reported to have been distrubed on November 11, 2018. Video shows the Af Ghiri shrine having been emptied of contents and the crypt located within having been broken open at the top, pointing to looting being a motivating factor.

Three months later, photos published by Afrin Activist Network show even more damage having been done to the interior tomb. So far, we have been unable to locate the shrine, given the scant geographic clues offered within the short video and subsequent photos.

The shrine is reportedly found in a wadi known as Biri, near the town of Qentere (here) of the Ma’abatli subdistrict. Images of a similar nearby shrine named Yagmur Dada, as well as further reading on Afrin’s Alevis, can be found here.

The official website of the PYDKS, a Kurdish political party historically strong in Afrin, reported on December 5, 2018 that a large shrine tree in the Sheikh Hamza shrine had been chopped down.

The oak tree, reportedly over 100 years old, was a prominent part of this shrine (located here) near the Bulbul village of Ze‘ire. It’s unclear what the motivation for chopping down the tree was, but there have been repeated allegations of militant groups illegally logging the region’s trees, including from its numerous olive plantations, for profit on the firewood black market. Pro-opposition news site Enab Baladi reported on this phenomenon in January 2019, interviewing locals who implied the complicity or guilt of local militant factions as well as the Turkish-backed Military Police.

On February 17, 2019, local Afrini activists posted pictures on Twitter showing that a sacred tree outside the Yezidi shrine of Sheikh Humayd had been cut down and that at least one gravestone in the surrounding cemetery had been knocked over.

Photos and videos published in the following two weeks show that multiple graves had been similarly vandalized and an entire portion of the shrine’s wall and roof had been knocked in. This makes four confirmed cases of Yezidi shrines being desecrated and/or destroyed.

The Sheikh Humayd shrine and cemetery are located here, between the historically Yezidi-populated towns of Qestel Jindo and Baflune, and on what had been the frontlines between PYD-controlled Afrin and the opposition stronghold of A‘zaz.

Afrin Activist Network published photos on March 25, 2019 showing a partially destroyed shrine named Sheikh Mohammed, located here in the town of Miske, Jandaris subdistrict. This destruction was actually first reported without imagery in October of 2018. The structural damage is clearly evident when examined by satellite imagery.

A sacred tree nearby was also reportedly destroyed and pro-PYD news agency Afrin Post reported that the town’s mosque had been looted, though this latter claim has not been corroborated. The shrine is presumably dedicated to a local Sufi saint as it is not mentioned in any Alevi or Yezidi source.

A third Alevi shrine (after Ali Dada and Af Ghiri), named Aslan Dada, was reported to have been desecrated by Afrin Post on February 9, 2019. A video shows that trees at the site have been chopped down and it appears that some contents of the shrine have been thrown on the ground. The video does not show the shrine itself so it’s hard to fully assess the damage.

As of yet, we have not been able to locate the shrine. Afrin Post reports that it is located south of the village of Khadiriya, in the Bulbul subdistrict. While this is a ways north of other Alevi shrines, the video appears to match the area’s terrain.

Curiously, an article from 2016 on several Afrini shrines that mentions Aslan Dada and appears to show the interior of the shrine, identifies its location as close to Julaqa, a town in the Jandaris subdistrict.

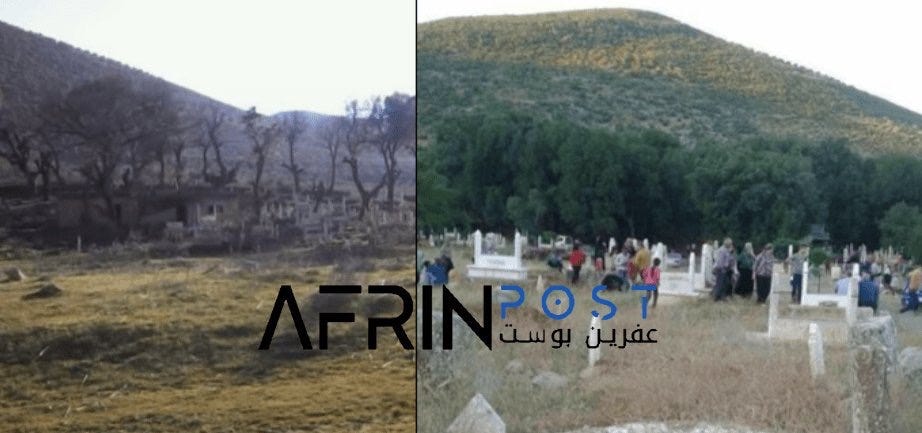

Regular cemeteries without shrines have also been targeted by vandals. A video published by the KLA on December 11, 2018 shows tombstones smashed and plots partially dug up in a cemetery located outside the village of Qurbe, in the Jandaris subdistrict.

On May 19, 2019, Afrin Activists Network posted a video on their Telegram channel showing a number of graves having been disrupted in the cemetery located outside of Qibare, east of Afrin city.

Prior to the war, Qibare was a predominantly Yezidi-populated town, and its surrounding countryside is home to three different Yezidi shrines. Currently the status of these shrines — those of Malik Adi, Jil Khana, and Hecherka — is unknown, but they are all located in close proximity to this cemetery.

First damaged by Turkish shelling in February, the YPG’s Martyr Seydo cemetery was further vandalized in the following three months. One of three YPG cemeteries in Afrin, the Martyr Seydo cemetery is located north of Jandaris and was constructed sometime before 2015.

The exterior of the graveyard suffered minor damage in February, due to shelling by Turkey or its allies, though it’s unclear whether or not this was purposefully.

However, pictures published on May 1, 2018 show significant intention damage to have been inflicted to the cemetery and numerous gravesites.

Given the emphasis on martyrdom in PYD political and military culture and extensive and intertwined use of party and militia symbology, a Turkish attempt to remove visual traces of their rival was likely inevitable — however the damage inflicted as seen in the April photos shows a large number of plots leveled and portions of the exterior walls toppled.

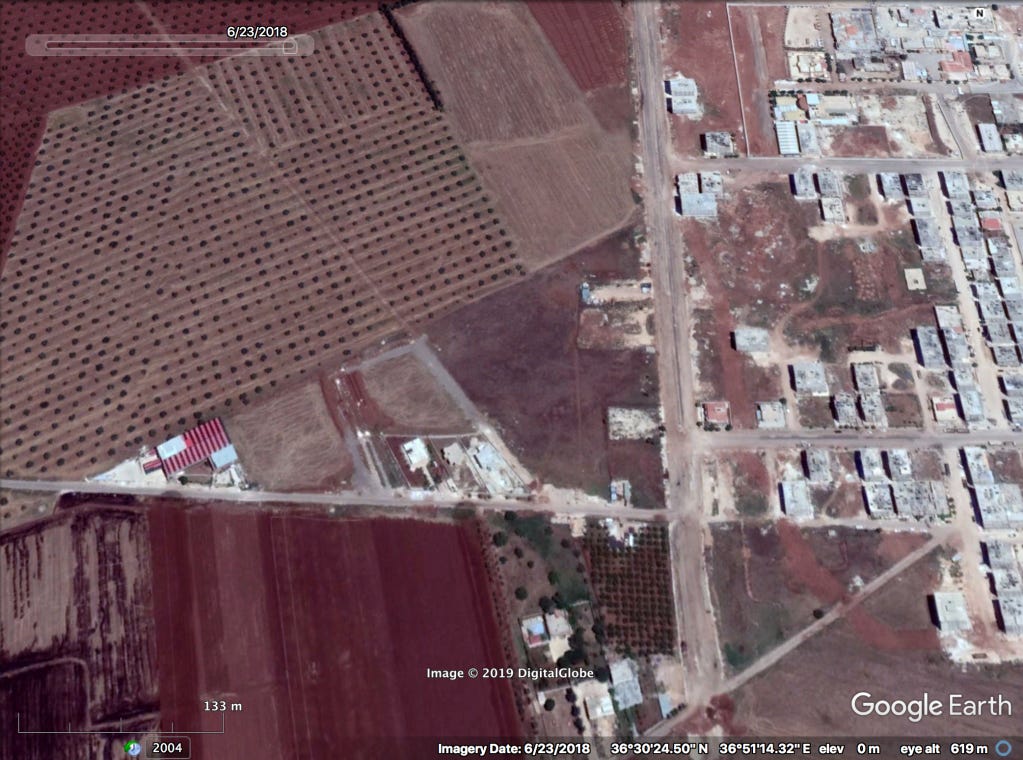

On August 12, 2018, a video was circulated by various Kurdish activist accounts showing the levelling of YPG’s Martyr Avesta Khabour cemetery located just west of Afrin city. The video shows a backhoe moving earth at the site in the middle of the day, just 250 meters from the outskirts of the city.

Closer images published at the same time show the ground covered in piles of dirt, rocks, and debris where the tombstones had been located.

Martyr Avesta Khabour cemetery, just an empty field until the start of hostilities in late January 2018, grew throughout the Turkish-backed campaign. Extensive footage of it exists in the form of YPG/YPJ martyr funerals.

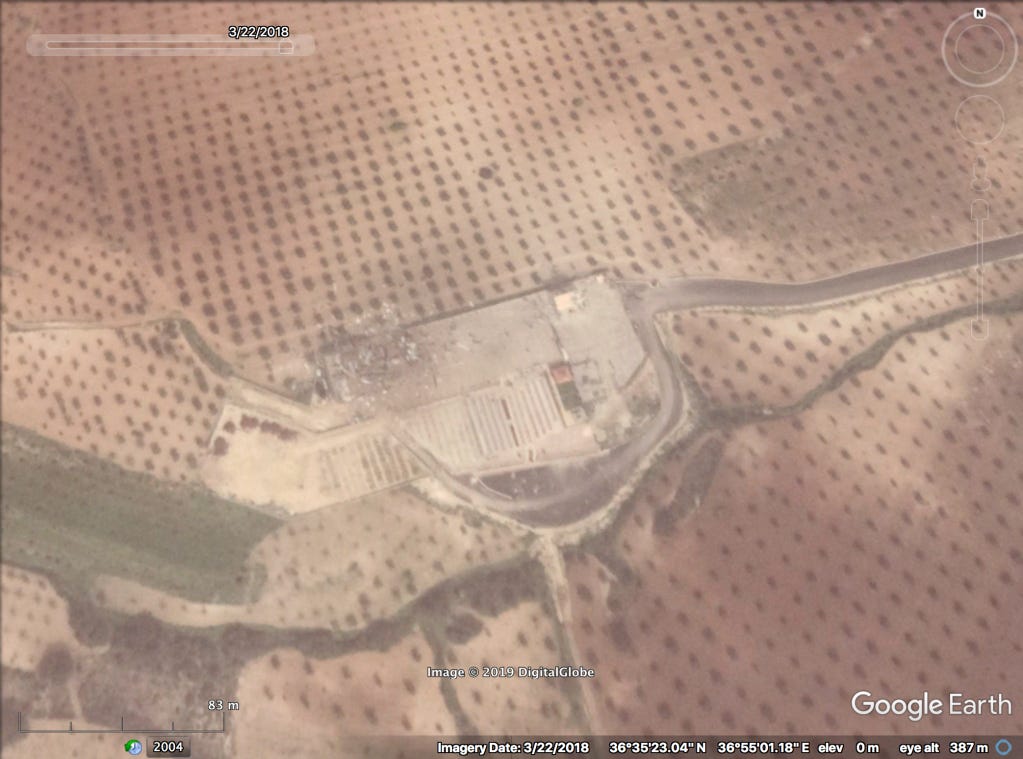

The third YPG/YPJ cemetery in Afrin, known as Martyr Rafiq, is located on a hill west of Qatme and was built sometime before July 2015. The site featured several pole barns nearby that can been in the background of funeral videos published prior to Olive Branch.

These structures were obliterated during the fighting, possibly by airstrikes. However, it is unclear from the satellite imagery whether the graves at Martyr Rafiq cemetery have been disrupted in a manner similar to the other two cases.

Days after the conclusion of Operation Olive Branch, Kurdish sources reported the desecration of 20th century Kurdish revolutionary Nuri Dersimi’s grave, located in the Henan cemetery near the town of Meshale.

Initially, the grave had four placards commemorating Dersimi, one in Arabic script and three in Kurdish using the Latin alphabet.

The former and one of the later have been destroyed and another one in Kurdish has been removed from the part of the tomb it rested on. Nuri Dersimi was exiled from the Turkish Republic after the Dersim uprising of 1938, and eventually settled in Afrin, where he died in 1973. Dersimi’s wife is reportedly buried within the same tomb.

On May 21, 2018, media outlet Deri Press published a video reportedly showing the Henan shrine, or Henan mosque, having been ransacked and looted. The mosque is located within the aforementioned Henan cemetery.

As we have not been able to find prior footage of the mosque’s interior, we are not able to conclusively match the location.

In a July 2018 Dars News report on abuses suffered by Afrini Yezidis following the conclusion of Operation Olive Branch, photos were published allegedly showing the destruction of a Yezidi cultural center and statues of the Prophet Zoroaster and the Dome of Lalish, in Afrin city.

This center was opened in 2013, and was home to the Yezidi Association. According to academic Sebastian Maisel’s Yezidis in Syria: Identity Building Among a Double Minority, this recently formed cultural organization formed committees assigned towards subjects such as “mediation, training, information, culture, sports, and women…[while opening] seminary schools…to…train teachers in Yezidi religious studies” in order to begin the education of the community’s youth.

This cultural center has been geolocated to the western side of Afrin city.

Through the analysis of satellite imagery it is clear that its destruction coincided with the capture of the city by Turkey and its allies. While it’s unclear what was used to destroy this building, lack of scorch marks and lack of disruption to the nearby foliage points to the demolition having been conducted by construction vehicles.

Via investigation of openly available material, it becomes evident that extensive damage has been inflicted on many heritage sites within the Afrin district of Aleppo. In particular, this has affected shrines traditionally used by the region’s heterodox religious populations.

Due to the fact that the perpetrators are only visible in the Qara Jorna video, we cannot definitively assign blame to specific parties. However, these incidents fall within the broader context of post-Olive Branch Afrin, in which armed groups and local councils have frequently been accused of human rights violations targeting the indigenous majority-Kurdish population.

The largely unsystematic pattern of these desecrations points to them likely being conducted randomly by different actors — for multiple reasons which range from religious or ethnic sectarian animus to personal gain through looting — it is clear that little to no effort has been exerted by the Turkish-backed governance bodies to prevent such incidents.